The monster appears, the whole theater jumps, and for a moment the digital surround sound system is drowned out by the whisper of a hundred held breaths released in unison. On the screen the characters crash through a hall, pursued by the relentless creature, ferocious and bloodthirsty and unstoppable. They don’t stand a chance. And yet, in this moment, the audience is weirdly relaxed. The Big Reveal is over, the monster has finally shown itself, and now it’s just a chase scene. The tension, coiled like a tight little spring just moments ago, has been discharged. For a few moments at least, the moviegoers can breathe a little easier and enjoy the afterglow.

Tension is an emotion rooted in delay. The job of the horror author is to set up a disaster and then stave off its arrival for as long as possible, to draw out the anticipation of it, to bleed the audience through tiny incisions but never cut the artery. The longer they can hold out the better the eventual payoff will feel, especially if they can use the interim period to make sure the central characters are worth caring for. And at the climax, when the truth is finally revealed, the better for it to be a startling truth, altogether different—and much worse—than the audience predicted. The best horror ends abruptly, the audience still in an almost post-coital daze, the implications of this final revelation still kicking around in their heads. The last five minutes of Psycho or The Shining or Cure or The Wicker Man or Sleepaway Camp or The Ring are designed to capture the audience in a warm embrace and knife them in the back at the same time. But it only works because tension has been built, bit by bit, over the previous 90 minutes.

The contradiction inherent to this kind of horror is that the audience will never make it to that golden reveal 90 minutes in without an early hook. They need to see something that primes the mystery, some early indication of the horror at hand so they can start building theories in their mind. Psycho kills its protagonist, the top-billed actress of the film, in the first 45 minutes. For an audience who went in expecting to see a movie about Janet Leigh, her almost immediate death is a dramatic primer. All bets are off—who knows where the story is going to go next. It Follows opens with its first and most gruesome kill, given just moments of screen time, to show the audience what the monster is capable of. The remainder of the movie shows progressively less and less—the audience has been primed and their minds will do the heavy lifting to create tension far better than any special effect. Cure and Seven are masterclasses in this trick, the latter’s major reveal requiring only an oblique visual suggestion and arriving just under three minutes before the credits roll. The primer hooks the audience early, sets up the engine for tension, and then lets exposition and imagination take the wheel. The horror director’s job is to slip a knife slowly between his audience’s ribs before twisting it at the very end, and to do that he needs to hook them early.

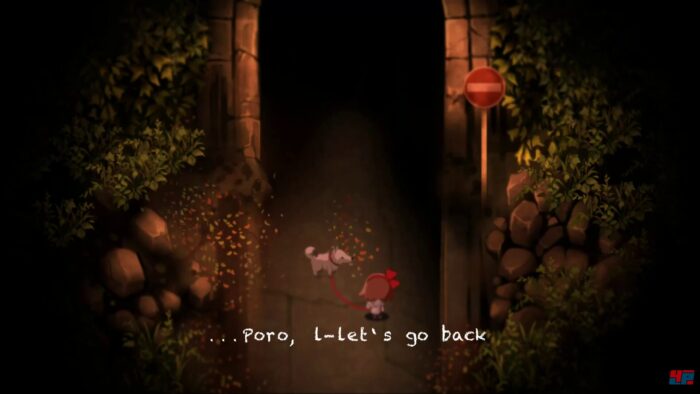

Landing a proper horror hook is hard for a 90 minute film, but it’s a nightmare for video games that won’t get around to their Big Reveal for five to twenty hours. It Follows can kill a girl in lingerie in three minutes to give you an idea of what to expect, but in a video game the primer must come very early, before it has a chance to introduce tutorials, power-ups, or any of the other structural ephemera that builds up over time to eventually reveal the core play loop. It’s like trying to get a kid headed to their first day of kindergarten excited about graduating high school. Silent Hill 3, Eternal Darkness, and even my own Dead Secret Circle open with a dream sequence in order to give the player a taste of the horror that they won’t see again for perhaps hours. Silent Hill‘s time-to-creepy-wheelchair is like three minutes, and Resident Evil gets you a zombie beheading in less than 60 seconds from start of play. Yomawari, in one of the best horror intros I’ve seen, wields its primer like a rusty fishook and embeds it deep in less than two minutes. Games have to hook you immediately and then sustain that hook for an eternity if they want to be able to really cut you deep at the end.

Landing the timing of that early hook is a hard design problem that I have struggled with. The original Dead Secret delayed the primer significantly–it comes, unexpectedly for many, nearly 30 minutes into the game–and I thought that was a pretty risky move. It worked out because Dead Secret presents itself as a detective game and then flips into horror when the primer fires, and that resetting of expectations made the hook effective. But you can only pull that trick one time. For the sequel, we went back to the tried-and-true intro-as-dream-sequence to whet the player’s appetite.

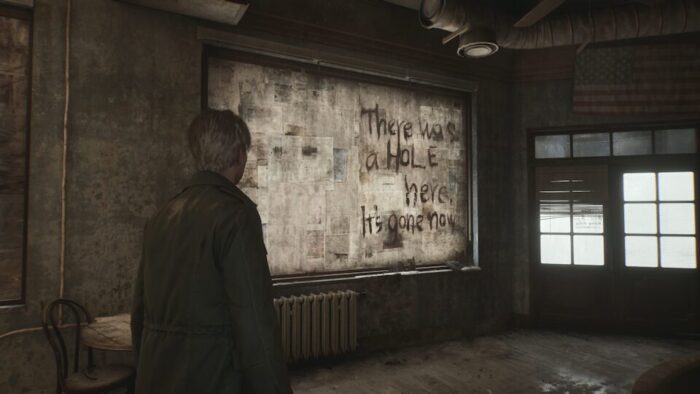

And yet, the rules don’t seem to apply to Silent Hill 2. Its introductory sequence is long, and slow, and full of dialog and aimless walking around. There’s an enemy reveal fifteen minutes in, but that’s not the primer. There’s no foreplay, no early hook, just constant and increasing levels of stress, stacked in layers of symbolism and claustrophobia. The tension delay is strong, but it takes a long time to coil. In a fascinating design decision, the excellent Silent Hill 2 Remake actually extends the length of the introduction, albeit by adding a few new traversal puzzles. In any other game, a big chunk of the audience would quit long before reaching the good stuff. Silent Hill 2 has an excellent Big Reveal, one that seemed shockingly mature in 2001, but how they heck did they away with such a slow burn?

Well, they didn’t. Not at first, anyway. Though Silent Hill 2 has sustained a powerful influence over video games for the last twenty years, its importance was not at all clear at its release. A common refrain in many critical complaints was the lethargic pace. Game Informer called Silent Hill 2 a “big fogging disappointment,” and “a sloppy, monotonous bore that nearly put me to sleep.” Gamespot’s review astutely noted that “many will come just for the progressive horror element and the possible gruesome unveiling of a horrible truth in the end,” but also found the title to be “smarter but less compelling” than its predecessor.

Silent Hill 2 survived its slow start, I think, because its eventual Big Reveal is so good. I am reminded of Audition, Takashi Miike’s 1999 thriller, which strings the viewer along for most of its running time before finally escalating into shocking horror, less a slow knife than a slow machete (or perhaps a slow wire saw is more fitting). Miike is insanely prolific, has directed over 100 films, but Audition is his best-known, at least in the West. I think both Audition and Silent Hill 2 won the audiences that stuck around through their quiet intros with the quality of the twist in the final moments, and that momentum carried them from fan favorites to cult classics. You can’t design a cult classic, they just kind of happen, but the big risk Silent Hill 2 took by eschewing a primer paid off for it in the end.

And maybe its the works that deny us the comfort of cliché, the films that refuse to prime their audience in an obvious way but nevertheless cut us deep at the end, maybe it’s those works that we remember as the scariest. The Blair Witch Project, Alien, Jacob’s Ladder, The Shining–many of the most famous horror films eschew the early hook1. But as I walk James through the newly-beautified mist clinging to the edges of Toluca Lake, I am reminded that there are very few games that can claim the same. The narrative that seemed so mature in 2001 feels stilted and awkward now, and yet, and yet, one look at the sales charts and it’s clear that Silent Hill 2 is still punching above its weight.

You can’t plan a cult classic, but I’m sure glad we have this one.

- I feel compelled to mention that Alien has one of the best primers of all time, a Big Reveal and Primer all wrapped up in one extremely deft chest-bursting scene. But it comes an hour into the movie, almost exactly at the half-way point. It is just one of so many interesting things this film does to keep the audience from relaxing. ↩︎

I would feel much more charitable towards the SH2 remake if they’d make the OG (or perhaps, Silent Hill 2 Enhanced) widely available at the same time. Post-move, I think have my SH2 PC discs around here, but many aren’t so lucky. You don’t put lipstick on the Mona Lisa and then make the lipsticked one the only version available.

/end TED talk

As an author, thank you for the structural layout of successful horror narratives. I’m scurrying back to my hole to archive this insight!

PS My husband wormed most his life as a first responder and most horror games make him roll his eyes. But he told me your first DEAD SECRET game really freaked him out!! So congrats!

That made my day! Thank you!

Informative and interesting article as always Chris, hope you have a nice end for 2024 and Happy early New Year! (Lurker for 10+ years, love your gaming and film analysis!)