My daughter turns three this week, so we celebrated by visiting Tokyo Disneyland (which, like Tokyo Game Show and the Tokyo International Airport, is not actually in Tokyo). The place was packed with families and couples (the latter of which take total control of the park after nightfall), but otherwise strongly resembled my blurry memories of the Disneyland in LA that I visited as a kid. The number of rides that are enjoyable by an almost-three-year-old are a bit limited, and the line for Dumbo rarely fell below 50 minutes, so we visited a random selection of attractions. Most of the rides amounted to a tour of a particular brand, rendered in black light, animatronics, and luminescent paint.

My daughter turns three this week, so we celebrated by visiting Tokyo Disneyland (which, like Tokyo Game Show and the Tokyo International Airport, is not actually in Tokyo). The place was packed with families and couples (the latter of which take total control of the park after nightfall), but otherwise strongly resembled my blurry memories of the Disneyland in LA that I visited as a kid. The number of rides that are enjoyable by an almost-three-year-old are a bit limited, and the line for Dumbo rarely fell below 50 minutes, so we visited a random selection of attractions. Most of the rides amounted to a tour of a particular brand, rendered in black light, animatronics, and luminescent paint.

In my memory of Disney LA, the best attractions were the roller coasters and the rides that weren’t tied to movie brands. Pirates of the Caribbean, for example, was fun to my 12-year-old self because it had clunky robot pirates with squirt guns. My favorite, of course, was The Haunted Mansion, which dumbfound me with its 1960s plate glass projection and rubber door technology. What impressed me most about that initial visit was how well-realized the various worlds in Disneyland are; though it’s obviously all sets and props, there’s a level of internal consistency that is extremely high quality, and lends an aura of convincingness to the whole affair. Many years later I read an essay about the rise of GUI operating systems by Neal Stephenson entitled In the Beginning was the Command Line, and I was struck by a passage about this very consistency.

Americans’ preference for mediated experiences is obvious enough, and … it clearly relates to the colossal success of GUIs and so I have to talk about it some. Disney does mediated experiences better than anyone. If they understood what OSes are, and why people use them, they could crush Microsoft in a year or two.

(Read the whole essay online).

What Stephenson is talking about is something he calls the “Sensorial Interface”–Disneyland as a user interface that serves to simplify complicated concepts and topics into easy-to-consume packages, just as graphical user interfaces on computers hide the complexity of running an operating system from the user. When I first read this passage it made a lot of sense: if you buy into the Disney version of the world, you can enjoy an afternoon in a simplified version of reality–a fantasy place where “dreams come true.” Not unlike a good video game, really; it occurred to me during one of the many rides we went on that there’s not so much difference between a Disney attraction and say, a rail shooter (and actually, some of the new rides are rail shooters). Consider the intro to Half-Life. Or any game that is intent on giving you a convincing looking but ultimately thin backdrop upon which to build its game play, which describes most games nowadays.

But after this last visit, I’m not so sure that Disney is firing on all cylinders anymore. Yes, all the pieces are there: Tokyo Disneyland is still a carefully constructed exercise in world building on a massive scale. But something has changed since I was 12, or perhaps it’s just that I’ve grown up enough to notice the seams in the carefully-constructed faux stone walls that border the property. But like a terrible script can mar a game with the greatest of graphics, something

Not charming.

The marketing of creative works seems to follow a predictable spiral; when a creative work becomes popular, it becomes a vehicle for monetization, usually via advertising, merchandising, and cross branding. Successful creative works have a tendency to attract complicated marketing apparatuses, which in turn require more creative work–or at least something resembling creative work–to continue to operate. Often, the marketing itself becomes the main vector of effort, until the core of the idea that originally made it popular–that spark that made it resonate with audiences to begin with–is lost. All that remains is a self-perpetuating marketing machine that operates on nothing but the lifeless husk that is the brand. The internet has provided a fantastic term for this transition: Jumping the Shark. I have discovered through my daughter that many famous films and books for children jumped the shark long ago: witness the series of Curious George books that were not actually authored by H.A. Ray, or the Miffy book that my daughter, at age two, correctly identified as a copy-paste job from several different stories by Dick Bruna. Absent any new content, the marketing machine can only press forward until it finally drives the brand into the ground.

I’m not suggesting that Disneyland itself has jumped the shark; as I wrote above, it’s still a marvel of engineering, and a lot of fun for kids. But certain aspects of the park have definitely sailed over that fanged fish and are now beyond recovery. That Dumbo ride with the 50 minute wait? It’s just your standard spinning rocket ride, available at any local carnival. It doesn’t even have a single black light.

Pirates of the Caribbean is a fascinating example: here we have the marketing machine spinning as it does, attempting to generate content from a thin but well-known brand (the original Disneyland ride), and against all odds the result is actually well received by critics. When handed this ultra-rare success, what does the marketing machine do? It replaces the old brand with the new one defined by the film, re-themes the original ride to make it look like the movie, and then goes about its merry way trying to drive this new film-based Pirates of the Caribbean into oblivion. The clunky pirate robots from my childhood have been replaced by ultra realistic Jack Sparrow clones that are incredibly articulate and yet lack all of the charm of their predecessors. The original ride survived unmodified for 40 years; will the Johnny Depp movies still resonate with audiences 40 years from now?

Which brings us, finally, to The Haunted Mansion (you knew I would end up here, didn’t you?). Apart from my obvious soft spot for things with horror themes, I particularly enjoyed The Haunted Mansion when I was a kid because it is rare to find so much energy put into something that is rather sinister. Stephenson’s point about Disney being experts at interface is strong here: the original Haunted Mansion carefully hits all the right thematic notes, while surprising and entertaining its attendees without actually being very scary. Nobody else knows how to make a sinister-yet-fun-and-not-scary theme

Thin ice.

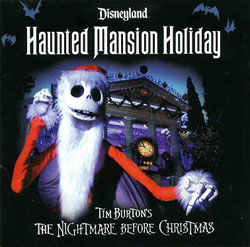

Or at least, I remember it being top notch. This time around The Haunted Mansion was easily the most disappointing ride that I tried (thankfully I spared my daughter; she was freaked out as it was by the Winnie the Pooh and Who Framed Roger Rabbit rides). In a blatant attempt at cross-branding, The Haunted Mansion is re-themed every fall to be a Nightmare Before Christmas ride. The Disney marketing machine initially attempted to recreate its Pirates of the Caribbean success, but when that failed they turned to the quirky (and generally fantastic) 1993 stop-motion animated film for branding backup (a cynic would note that Disney had no hand in the original production, which is perhaps why the movie was good in the first place). Anyway, despite being based on a pretty good movie, the Nightmare Before Christmas / Haunted Mansion mashup is a total failure because the combination of the two brands serves no purpose. The Nightmare Before Christmas characters appear instead of regular ghosts, snowy christmas trees are inserted into already existing scenes, and around every corner is a Jack Skellington auto-animatronic; clearly the goal here is to service the Nightmare brand. The Haunted Mansion isn’t improved–to the contrary, its careful balance of theme consistency and entertaining spooks is completely destroyed by the injection of this foreign brand. The result is a mess–it’s not very fun, it’s not very spooky or sinister, and it’s not even a very good vehicle for the Nightmare characters because it doesn’t play to any of the strengths of that brand. It’s a combination borne, I think, of convenience; there are no other Disney rides that have sinister themes, and thus no other place that the marketing machine could conceivably plaster the Nightmare brand.

If there’s a point to all this, it’s not just that marketing often serves an anti-creative purpose. It’s that horror in particular, being a genre defined by theme rather than by content or presentation, is vulnerable to this kind of careless brand pollution. Disneyland works very hard to present to you a believable world, but its work is sabotaged by its need to somehow integrate modern brands into existing attractions. Nowhere is this more evident than The Haunted Mansion, and I think the horror theme of the ride itself relies on a carefully calculated, easily disrupted combination of elements. The insertion of an unrelated brand destroys this balance, and renders the entire ride pointless.

The takeaway implications for horror games are that world consistency is key to believability. When the seams start to show, be they jarring juxtaposition of brands or, say, bugs with collision detection, they instantly render the fiction of the game moot. Other types of games can get away with a few flaws; some might even benefit from a little real-world branding (Wipeout XL?). But horror games rely on world believability above all else, and often trade other important elements (such as tight player controls and complex combat systems) in order to increase that believability. Just as The Haunted Mansion is rendered impotent by the grafting of the Nightmare Before Christmas, when a horror game suffers damage to its fiction, there’s no reason to keep playing.

The last theme park I visited was Alton Towers and it did indeed have a horror themed “rail shooter” ride, the thing that killed it for me was the theme park was affiliated with energy drinks, promoting the idea of an adrenaline rush.

So we get started on the ride, and about 4 or 5 set pieces in, a zombie swings out, which naturally I started shooting, only to notice the Red Bull can in its hand.

There’s an attraction making its way around the UK at the moment called “Alien Wars” a sort of guided tour around a maze of dark corridors while being chased by the Aliens made famous by the films.

A friend of mine tried it out when it was in Glasgow and said it was terrifying, he also said that they had went the extra mile to make sure all the sound effects (weapons, alien noises etc) where the same as those in the films, which really added that extra curtain to the fact you were being chased by guys in rubber suits around a music venue, and guided by an actor who had already ran through it 20 times that same day.

Check it out –

http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_profilepage&v=iDspb_wxevw#!

http://twitter.com/#!/matty_125

I was always disappointed when I would to Disneyland and see that *someone* tacked on a character from ONE decent film over these beautifully crafted designs of ghosts.

If you noticed though, the branding isn’t as agressive as it was once getting. (with the exception of Phantasy Star Online’s Pizza Hut and Sanders). Or, maybe it’s more subdued now and people just don’t care to notice?

Either case, even though the content may be good, branding does push me away a bit, such as a certain “kingdom” game, or at least pique my ears.

Anyway, one thing that Tokyo Disneyland has over the one in Anaheim (er, or, L.A.) is the Halloween fireworks show.

Two words: Silent Hill.

@Somber: Not really. “Resident Evil” is a FAR better choice of two words. At least Silent Hill is TRYING to keep that spark alive.

@Sadness

Agreed. Silent Hill lost something when Konami started passing the brand around to various western studios, but Resident Evil is barely a horror series anymore. Case in point: they got rid of zombies. Resident Evil… stopped using zombies.

But anyway, back to the main article. Reading this, I got to thinking about how developers can improve the consistency of their game worlds by bringing elements of those worlds into real life. Take the Siren series, for example. Part of the marketing for every game included a number of fake websites and blogs that provided more information on the locations, characters and plot elements while maintaining the illusion of reality. It really added to the experience.

Consistency doesn’t have to remain within the confines of the game itself. We can manipulate what goes into it, and what thread connect the real world the game world to surprisingly good effect.

Yeah, neither Silent Hill nor Resident Evil have much to do with what I am talking about.

Change over time is normal. That happens to every sort of creative work that appears in a series. You might not like the new direction, but there’s a difference between the creators trying something new and the creators abandoning the entire project, leaving marketing to somehow try to compose new content from the scraps. That certainly hasn’t happened to either of those series yet (though I do admit that the Silent Hill Arcade Shooter is pretty bad).

Think of it this way: if you like a band’s early albums, but then on their most recent release they totally change style and you don’t like them any more, that’s just a matter of taste. Compare that to a band who gets real popular and then disbands (or, as happens pretty frequently, the lead dies). After that there is no new content, but the band is so popular that the marketing folks can’t leave it alone. That’s when you start to get music videos for demos recorded when the band was in high school (which do not actually feature the band members). Eventually it degrades to like lunch boxes with the band logo on them, and NEVER FORGET t-shirts with close ups of the dead lead. THAT is when the marketing machine has driven the brand off of the cliff.

I have to disagree with you there, Chris. With Team Silent not being involved in the Silent Hill series anymore, it DOES feel like the lead singer has died and all the members have changed. Silent Hill is an established brand and with the Movie and the ho-hum games that have come out, I feel like it matches your band/marketing cash-in analogy pretty exactly.

That being said, I like the Silent Hill series so much that I get excited, even for the uninspired sequels.

> Lasant

I’m drawing a line in the sand between “uninspired sequels” (which is not what I’d call the recent Silent Hill and Resident Evil games, but that’s a separate argument) and “exploitation of a brand without any new content.”

We can talk about uninspired when Silent Hill gets a saturday morning cartoon starring Triangle Top, the cute super-deformed version of Pyramid Head, who subsequently starts to appear on the back of pink backpacks designed for first graders. That’s basically what’s happened to The Haunted Mansion.

I think we’re splitting hairs, here. The direction that both of these series’ are taking is worth talking about and I can see how it’s relevant to your article, even if it’s not a direct parallel.

I guess my point is that even if these beloved games aren’t in the state you specify, they appear to be moving in that direction. I’m sure no expense was spared when they made those animatronic Jack Sparrows just like Silent Hill: Homecoming was by no means a low-budget title. The “seams” that you speak of, for me, are when I see elements thrown into a game that would never be there if it were someone’s “baby.” Things that only appear to be included to increase marketability. In homecoming, the most obvious of these elements would be the inclusion of Pyramid Head (because he was in the movie!) and the mine/miners/coal-ash (because they were in the movie!). And the movie!??? It hurts because it was almost good 🙁

P.S.

I lovelovelove the comparison of mediated experiences to GUIs.