Also known as: Jack is Back

Platforms: PSX, Saturn, PC, Mac, 3DO

Release Date: 1996-08-22

Regions: USA Japan Europe

Dark Messiah

Also known as: Hell Night

Platforms: PSX

Release Date: 1998-06-11

Regions: Japan Europe

Chris’s Rating: ★★★★

Obscure for no good reason, Hellnight shows us that really well designed horror games can be scary even with only the most rudimentary technology at their disposal.

Hellnight (Dark Messiah in its native Japan) is one of those games that is occasionally mentioned in lists of under-appreciated masterpieces; it’s the type of game that is fantastically popular amongst the very few people who have actually played it. It was only released in Japan and Europe, and in both regions it never escaped obscurity. I finally got around to playing it myself after I realized that my new digital TV can render PAL signals (almost) perfectly, allowing me to finally use the European version of the game that 16bitman donated to the Quest a few years ago. And now that I’ve played the game through, I am very happy to join the small (but outspoken) club of people who think that Hellnight is an absolute gem of a horror game.

The premise of Hellnight is simple: on the way home one evening, the subway car you are riding in is attacked by some sort of monster and almost everybody on board is killed. You and another passenger, a schoolgirl named Naomi, manage to escape into the sewer system, but you soon realize that the monster is hot on your heels. With no way to fight or otherwise defend yourselves, you and Naomi have no choice but to run away and try to find your way to the surface. But as the monster closes in, you are forced deeper and deeper underground, and after a while the things you discover in the depths make your pursuer seem like the least of your problems.

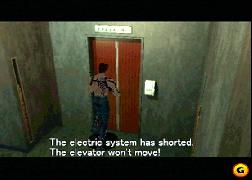

The game mechanics in Hellnight are also very simple. The game features two modes: a 3D, first-person perspective mode in which most of the game is spent moving through underground passages and trying to avoid the ever-present monster, and an exploration mode that uses static pre-rendered images to represent searchable rooms and conversations with other people. In the 3D mode your only controls are related to movement; you can walk or run, look around you, and interact with some objects in the world. If you run for too long without a break you will become tired and eventually die. In the 2D mode, you can only select interesting looking things and interact with them. It’s like a cross between Doom and Myst, only without any shooting or clock puzzles. The bulk of the game play involves searching each maze while trying to avoid running into the monster. If the monster ever catches up to you, his strike will kill Naomi first, and if you get hit again after that it’s game over. No life bars, health drinks, or continues in this game.

The key to Hellnight is that it takes an extremely straight-forward idea and turns it into an enthralling horror game by focusing heavily on specific elements of the design. Sure, the 3D graphics are terrible by today’s standards (or even by Dreamcast standards), but the sound design is phenomenal. The cut scenes bear the mark of mid-1990s computer graphics, where everything is sort of oblong and shiny and appears to be moving in slow motion, but the story that is told with this dated art style is fascinating. The game play is indeed incredibly simple, but the level design is so fantastic that the experience is constantly fresh and rewarding. In short, Hellnight is a shining example of how to make a horror game without relying on technology, big budgets, or “deep” mechanics. Hellnight only does one thing, but it does it really, really well.

If you’ve played any of the Resident Evil games before

Resident Evil 4, you’ve probably found yourself stuck in the wrong safe room at least once. You’re in the safe room and you know exactly where you need to go, but you are too low on health or ammo to actually fight your way to your destination and you know that all potential paths are full of zombies. So you make a run for it, deftly avoiding the zombies and creatively altering your route in order to make it through the gauntlet to the next save room. These moments are extremely stressful, as any misstep usually means death, but they are also incredibly rewarding. The level of tension as you run past a group of zombies and jam the X button to open the door is high, and such moments are one of the highlights of the Resident Evil series.

Hellnight takes that brief moment from Resident Evil and makes an entire game out of it. There’s no hope for survival if you actually meet the monster in some dark corridor, and so every step must be taken with care. You have some warning that the monster is coming, mostly in the form of the sound of the monster’s heavy footfalls, but you can never be sure which direction he is headed in or if you’ll be able to escape if he shows up in front of you. The level of tension produced by this game is astounding, especially considering the extremely dated visuals. The feeling of accomplishment that the game induces was also startling; I was surprised at the immense sense of relief I felt when I finished the game.

The dark, claustrophobic environments that the game takes place in certainly contribute to its scare-factor, but I think that the sound design is actually the key to Hellnight’s success as a horror game. The sound is spare and ominous; what little music there is quiet and unassuming, and its lack of dramatic crescendos increases the level of tension. The only other sounds are those the monster makes, mostly grunts, growls, and footfalls, and the beating of your own heart, which increases as you run for sustained periods. This sparse approach to sound reenforces the feeling of isolation and hopelessness that the story and visuals have created, and is a key part of the winning formula that Hellnight employs.

In addition to the excellent horror elements, the game design itself is very interesting. The story branches and changes depending on how you play; if Naomi dies and you are able to escape, you can eventually meet and partner with other people, which causes the story to change significantly. Towards the end of the game some things change, and the characters that have been introduced thus far are made much more interesting. Finally, though most of the traditional puzzles are standard item fetch quests, the meta-puzzle in Hellnight is encoded in the level layout: in each level you must identify loops and exits so that when the monster arrives you have a way to escape without backtracking. The difficulty of this traversal puzzle gets cranked way up at the very end of the game, but again, it’s extremely rewarding to complete.

There are a few problems with the game, but most of them are so minor that they are hardly worth mentioning. This is a ten year old game, old enough that it lacks DualShock support, and some of the nuts and bolts of the game play lack a level of polish that we’ve become spoiled enough to expect. Specifically, it’s sometimes possible to get stuck in collision, especially on a moving walkway, which can mean death when you are being pursued by a giant hyper-evolutionary monster. The game also really needs a quick turn around button. Still, these complains are exceedingly minor; the whole game works so well that there’s really very little to find fault with.

Hellnight is proof that horror games do not need to rely on technology to be good. Even with rudimentary graphics and game play systems, Hellnight is an incredibly scary game. Part of the premise of my research on this site is that game design decisions that focus on horror are much more important than the actual details of the implementation, and Hellnight seems to go a long way to proving that theory out. I highly recommend Hellnight to anybody who is interested in horror games; it is fantastic.

Countdown: Vampires

D

Also known as: D no Shokutaku

Platforms: PSX, Saturn, PC, 3DO

Release Date: 1996-03-02

Regions: USA Japan Europe

Chris’s Rating: ★☆☆☆

One of the only mid-1990s first person pre-rendered puzzle games worth remembering.

D is sort of a Myst-style horror game. It is played from a first-person perspective, and is built exclusively out of pre-rendered images. This game is the first entry into WARP’s D Series (D no Shokutaku; “D’s Dining Table” in Japan), three games with unrelated plots that star the same female protagonist. Kenji Eno, WARP’s founder, lead designer, and main musician, was interested in the idea of virtual celebrities, and wanted “Laura” to become a brand tied to no particular game design. The plan does not seem to have been successful; after D2, WARP changed its name and exited the game business.

Nonetheless, D is an interesting game. The plot, involving Laura attempting to find her way through a hospital to her psychotic father, is interesting. Throughout the quest, Laura witnesses a series of psychedelic flashbacks that reveal her own repressed past, and though the adventure is entirely point-and-click, the story is well conveyed. The graphics are quite dated by today’s standards, but they looked top notch when D was released in 1996.

D suffers from its incredibly short length. Though the hospital is fairly large, the puzzles are easy and the entire quest can be completed in a few hours. The gameplay is mostly consistent, but there are a few puzzles (and one annoying realtime section) that simply do not fit. However, WARP did a pretty good job overall, and D is one of the few unique games in the horror genre.

Parasite Eve II

Parasite Eve

Silent Hill

Clock Tower 2: The Struggle Within

Also known as: Clock Tower: Ghost Head

Platforms: PSX

Release Date: 1999-10-28

Regions: USA Japan

Chris’s Rating: ☆☆☆☆

Fascinating game mechanics and a truly unique approach to the horror genre is marred by inconsistent rules and trial-and-error game play.

I really, really wanted to like Clock Tower 2: The Struggle Within. The Clock Tower series employ game mechanics quite unique to the horror genre, and are built upon some very creative design ideas. Clock Tower 2 is no exception, and though it gets a lot of things right, one or two major flaws keep it from being successful.

As with previous Clock Tower games, The Struggle Within is controlled via a point-and-click interface. Though the game is 3D, characters are moved around using a cursor to click on doors and objects. The pathfinding is fairly intelligent, and the interface works well (though the mysterious lack of a “walk in this direction” button makes the game more difficult to control than previous versions). The analog stick support in particular makes wielding the cursor easier than it has ever been.

One of the unique features of the Clock Tower formula is that the main character–always a high school-age girl–is unable to actually fight off the game’s enemies. Instead, her only option is to run and hide, a mechanic which definitely increases the tension and makes the game quite scary.

Clock Tower 2 adds more depth to the mix by giving the main player a split personality disorder. The main personality is Alyssa, a normal teenager. The secondary personality is Mr. Bates, a coldhearted killer who takes over when Alyssa becomes frightened. Alyssa carries an amulet that prevents Mr. Bates gaining control, but the game allows you to put the amulet down and force Bates to come out. As Bates, the player has access to different areas of the environment, and can use weapons against the enemies. The game narrative is developed through in-game events, and since Alyssa and Mr. Bates experience events differently, much of the strategy involves switching between the two personalities.

The dual personalities are done very well. When controlled by Mr. Bates, Alyssa speaks in a deep Hannibal Lecter-like male brooding voice. When confronted with blood or gore, Alyssa will often cry out in terror, while the same scene is libel to make Mr. Bates laugh. Bates also swears all the time, and the two characters are so different that you look forward to seeing how each will react.

While the dual personality concept is very cool, the actual implementation is a little iffy. The biggest problem is that there is no logical reason that Mr. Bates should be able to open doors that Alyssa cannot. Throughout the game, doors that are available to one personality are simply unselectable by the other. Since no explanation is offered, this particular flaw reminds us that we are playing a game, and does significant damage to our suspension of disbelief.

Clock Tower 2 consists of three chapters, each featuring a different threat and gameplay style. Decisions made in early chapters can affect events later in the story, and the game features 13 different endings (most of them result in the death of your character). However, herein lies Clock Tower 2‘s greatest flaw: the game allows the player to make decisions that will force them to lose later in the game. Even worse, the outcome of such decisions is never clear, and sometimes the player is not even aware that a decision has been made. When a “bad” state has been reached, the player’s only recourse is to start the entire game over. You read that right: there is no way to go back and correct “mistakes” made earlier in the game. And since there is no obvious correlation between actions and outcomes (why does speaking to a character as Mr. Bates cause a less-than-perfect ending?), there is no way to tell where a mistake has been made.

For example, at one point in the game you must lock an enemy in a room in order to progress. However, the game never explicitly states that such an action must be performed, and skipping the action produces no immediate affect. If you save your game after failing to lock the enemy into the room, you are screwed: there is no way you will be able to progress without dying. Your only recourse is to start the game over.

This happened to me twice: once at the beginning of the game and once at the end. I reached the end of the game and found that certain doors are simply not available, and that there was nowhere to go. This means that I made a mistake somewhere in the previous two chapters (meaning I probably failed to see an event or something), but since I have no idea where such a mistake might have been made, I have no choice but to start again from scratch. This is unacceptable, and lowers the overall quality of the game by close to 20%.

My recommendation is to play through Clock Tower 2, but don’t spend much time trying to get events to occur in the right order. There is no way (save trial and error) that you can divine which events are “correct” and which are not, so do not even try. If you get stuck part way through (which will almost certainly happen), restart and use a walkthrough from GameFaqs.com.

Clock Tower 2 is almost a great game, and its unique and quirky ideas almost make it work. The flawed progression mechanics, however, ultimately ruin the entire experience.