The camera system in Fatal Frame 2 is fantastic.

This is the last part of a three-part series of posts about how camera systems and character movement have evolved over the last ten years. In

part 1 I discussed the problems that horror game developers faced when transitioning from 2D games to 3D games, and in

part 2 I talked about the ways improvements that were made to camera and control systems in the second wave of horror games. In this post I’d like to touch on how these camera and control schemes fair today, and mention a few games that have diverged from the norm.

The primary problem developers face nowadays is how to mix different types of camera systems (fixed cameras, cameras that follow the player, cameras that are tethered to a pre-defined path) in a way that doesn’t make the control scheme impossible to deal with. As I mentioned last time, the Parasite Eve model was popularized by Devil May Cry and remains the approach of choice for most fixed (or mostly-fixed) camera games (think Ninja Gaiden and God of War). Many games have abandoned the fixed camera approach all together and instead focused on smart follow-cams, which usually don’t cut and therefore do not suffer from the problem of “forward” changing definition. The games that do mix follow and fixed cameras need to be careful: you can see the system break down in games like Siren where one mode makes perfect sense and the other is jarring whenever it occurs.

One game that deserves special mention for its intelligent mixing of cameras and controls is Fatal Frame 2: Crimson Butterfly. The camera system in Fatal Frame 2 is phenomenal; it includes fixed cameras, cameras that follow a path, and free-roaming follow cameras. In addition, its control system is robust enough to deal with all of these different permutations. In the intro sequence to this game where the protagonist approaches the cursed village, we are treated to some extremely complicated (from a control point of view) camera shots (cameras following a curve, shot from above, and cutting in 180 degrees), and the system is so smooth that most players probably didn’t even notice it. Though Fatal Frame 2 relies on a fairly standard RE-style character-centric system (though it’s perhaps a little more sensitive than most other games), on of the keys to its success is that the run button can be held down to move the character forward without any stick input. This allows the player to move forward in a camera-independent way without relying on difficult character-centric movement. Though the Parasite Eve “sticky” camera-centric control scheme would probably have been a better choice for new players, the addition of the run button-based movement removes much of the pain caused by the tank control model. Once the player realizes that this is possible, movement in Fatal Frame 2 becomes a breeze: the player needs only to hold the run button down and make minor adjustments to the left or right in order to drive the character through the environment. Coupled with the vast array of camera behavior that Fatal Frame exhibits, I think that this is an extremely successful example of how to do controls in a cinematic game.

Fatal Frame 2 isn’t the only game to use a button to move the player forward.

The Resident Evil Remake contains one of the best tank control models ever in its “Type C” control scheme.

The excellent

Resident Evil Remake offers the player a couple of alternate control schemes to choose from, and one of them, “Type C”, is by far the best. Under the Type C control scheme, the right trigger button is used to move the player forward, and the analog stick is only necessary for turning left and right. This is fundamentally the same as Fatal Frame 2’s run button movement, but it works even better in this context because the GameCube controller’s trigger buttons are big and analog. Push the button down part way and the character walks forward, but clicking it down completely will cause him to run. The depth of the button on the GameCube controller gives the player far more control over their movement than analog-stick based systems, and since Resident Evil players are used to holding a button down to run anyway, it’s not any more work than normal. In fact, the system works so well that I wish that it were available in every Resident Evil game; the ability to run forward without using the stick and without relying on the direction the camera is looking makes the dreaded tank controls a walk in the park. Unfortunately this control mode didn’t make it into the subsequent Resident Evil game on GameCube,

Resident Evil 0, probably because that game required the player to use the analog stick and the C-Stick to move two characters around.

The last game I’ll mention here is Resident Evil 4, which is noteworthy because it effectively merged character- and camera-centric controls. In Resident Evil 4 “forward” is always defined by the direction that the camera is facing, but at the same time “forward” is always the direction that Leon is facing because the camera and Leon are almost always focused on exactly the same point. Unlike many other camera-centric first person games which feature slightly divergent camera and player facing directions (so required because you usually can’t see through your character’s back), Resident Evil 4 is able to align the two by bringing the camera in very close to the character, and leaving it there for most of the game. This makes Resident Evil 4’s control and camera scheme more like a first-person shooter than like traditional third-person games, but it works very well. The camera is able to move in and out of its normal position to show the floor around Leon, or to convey a sense of claustrophobia, but generally it remains looking along a vector that intersects Leon’s eye direction right in the middle of the screen. This is a very interesting approach, and is clearly the result of a lot of research and development by Capcom.

I’m very interested to see how camera and controls continue to evolve in the future. Games like Gears of War have already appropriated horror game mechanics for other types of games, and I think we’ll see horror games adjusting themselves in the future as well. The recent Silent Hill 5 footage, for example, suggests that the most recent game in that series may use a significantly different approach to cameras and movement than previous games in the series. These two systems, control and camera, are central to the way horror games look and feel, and I think that there is still a lot of ways that existing systems can be improved.

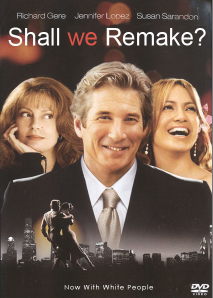

You can learn something about the American economy by watching horror movies. It’s true: when times are good and Hollywood is less risk-averse, we are treated to subtle, interesting, and original horror movies. When the economy is shitty (I hate the word “downturn,” it’s so saccharin), Hollywood responds by reverting to tried-and-true vehicles for turning a profit from teenage audiences (read: whatever worked before; usually sex and gore). During these times the penny-pinchers are looking for “sure bets,” films that they can count on to make a profit, even if that profit isn’t ultra blockbuster. I think that there is probably enough historical evidence to make a Horror Film Quality economic index at this point.

You can learn something about the American economy by watching horror movies. It’s true: when times are good and Hollywood is less risk-averse, we are treated to subtle, interesting, and original horror movies. When the economy is shitty (I hate the word “downturn,” it’s so saccharin), Hollywood responds by reverting to tried-and-true vehicles for turning a profit from teenage audiences (read: whatever worked before; usually sex and gore). During these times the penny-pinchers are looking for “sure bets,” films that they can count on to make a profit, even if that profit isn’t ultra blockbuster. I think that there is probably enough historical evidence to make a Horror Film Quality economic index at this point. audiences (

audiences ( Thanks to

Thanks to

As I’ve mentioned before, I’m a big fan of Japanese director Kiyoshi Kurosawa. As a filmmaker, he’s able to manufacture creepiness with lighting, shot composition, and sets alone. The actors (and ghosts) that populate his scenes are sometimes just icing on the horror cake: Kurosawa knows how to design his films to maximize scares better than any other director in recent memory.

As I’ve mentioned before, I’m a big fan of Japanese director Kiyoshi Kurosawa. As a filmmaker, he’s able to manufacture creepiness with lighting, shot composition, and sets alone. The actors (and ghosts) that populate his scenes are sometimes just icing on the horror cake: Kurosawa knows how to design his films to maximize scares better than any other director in recent memory.