Yep.

Casey, my founding partner at Robot Invader, is a huge Dark Souls fan. So are a number of my friends. Many designers I respect immensely have told me that they consider Dark Souls to be one of the best games ever made. People talk about it with such reverence, I feel like I am missing out. But every time I’ve tried to play the game seriously, I’ve felt that I was wasting my time.

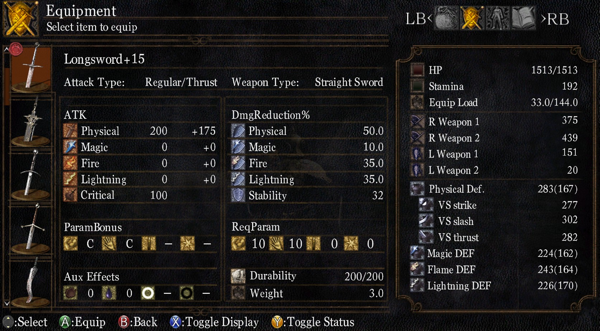

The problem isn’t the difficulty. Dark Souls is incredibly difficult, but I’m sure that, with time, individual enemy encounters become more manageable than they are in the early game. One should at least become proficient with the combat system and controls, and can eventually upgrade stats and weapons. Combat might not be easy, but over time it probably seems less random. I am cool with that–I have enjoyed some pretty hard games that worked much the same way in the past. I am proud to have finished God Hand, Devil May Cry, Catherine, Siren, and the arcade version of Strider on less than $2, way back in the day. Once I did a zero continues run of Resident Evil 4. It could be that Dark Souls is just too hard for me, but I don’t think that’s the real issue.

Even after playing for what seems like a long time, I’m absolutely unable to make any progress. Perhaps I’m just playing it wrong. Maybe I’ve made some grave error in my perception of how this game is to be played, and because of that I’m making it much harder on myself than it should be. Is the first boss supposed to take 100+ attempts? Or did I screw up somewhere?

The feeling of wasting my time comes from the basic sense that I’m zigging when the game expects me to zag. This is reinforced by the occasional discovery that I have be doing it all wrong. For example, early in the game your character is told to that they can go “up or down,” but that up is the easier path. The path downwards, a series of winding stairs heading straight into the face of a cliff, is easy enough to find. The path upwards is a small staircase placed at the side of a cliff that I completely missed my first time through that area. I missed it the second time, too. And about fifty other times. I explored the area and the only other place to go, other than down, seemed to be through a graveyard into a cave. I spent a few hours trying to fight my way into that cave, and eventually made it, only to be killed immediately by even more powerful enemies. Skeletons in Dark Souls are no joke.

“Don’t go that way,”  Casey said, when I asked him about it.

Casey said, when I asked him about it.

I eventually found the way up, and breezed through the next area until I reached a boss, whom I’ve been unable to defeat in the subsequent 10-odd hours of play.

“You’ve just got to get better,” Casey said. “That’s the fun part.”

But better at what? Combat? Better weapons? Better stats? Better at finding my way through the map?

The real issue, I think, is the way the game refuses to give the player feedback about their decisions. The rules are complex and the path to the goal is intentionally obfuscated. Am I going the right way? Which character type should I choose? Which gift? Which stats should I upgrade? Should I upgrade all my stats little by little or pour all my points into one or two abilities? Am I meant to come back to this area later or have I just missed some trick to completing it? Should I spend humanity points or hoard them for later? My experience is that the play outcome for me, for all permutations of the above questions, is the same: I die in the same spot over and over and over again. It doesn’t seem to really matter which choices I make; maybe it will matter 60 hours in, but at the 15 hour mark the complete lack of feedback from any of the decisions I’ve made leads me to feel that they are pointless.

There are other hard games that refrain from holding your hand as you play. I think pretty much everybody hit a shelf moment when they encountered the very first lava spider boss in Devil May Cry. You’re meant to figure out that you need to grind for upgrades, or simply become incredibly good at playing, or select the easy mode. That boss is a forcing function: you learn how to play or you adjust the difficulty or you quit. And once you’ve passed this moment, you have a better idea of what is expected of you as a player, and the game now knows something about how you choose to play. But a lot of people I know just gave up at that point. Siren is another hard game that does a terrible job of telling you the “correct” way to play, and you can get lost for hours on end, making no progress whatsoever, until it clicks. When it does, it’s an amazing game. But a lot of people quit long before they get there.

I’m ready to believe that there is a threshold of understanding to Dark Souls, and surpassing it makes a number of unanswered questions clear. That inflection point probably makes it more clear what the game expects of you, and you can start to strategize and make informed decisions. But until you reach that point, you’re flying blind. Dark Souls isn’t going to tell you if you’ve chosen the easy road or the hard road, or even if you’re on a road that is going anywhere at all. It’s not going to tell you if your approach is advantageous or problematic. It’s not going to tell you what it expects you to do.

So, I guess you can stick around long enough to figure it out, or you can become frustrated with the absolute lack of progress or feedback and quit. After 15 hours of feeling like I have no idea what I am doing and am wasting my time, I quit.

Given the tremendous glut of mobile games available today, it surprises me that there aren’t more horror games. There are a number of zombie shooters, a bunch of Halloween-themed games, and some interesting text adventures, but very little designed to actually scare you. Other than

Given the tremendous glut of mobile games available today, it surprises me that there aren’t more horror games. There are a number of zombie shooters, a bunch of Halloween-themed games, and some interesting text adventures, but very little designed to actually scare you. Other than  Every once in a while I get an angry message asking me why I omit PC games from this site, or why I fail to include visual novels and light gun shooters. The reason is mostly logistic: I have a limited capacity to buy and play games and so I need to contain my research in some way to make the project feasible. When I look at the number of PC horror games that have ever been made, and the lengthy steps required to purchase and run these games, it is an easy decision to avoid them purely on cost/benefit grounds. The same can be said for visual novels: the form is slow, there are a ton of them, and I don’t expect to learn a whole lot about how horror games can be made by reading text set against static images (even when the text is really good!).

Every once in a while I get an angry message asking me why I omit PC games from this site, or why I fail to include visual novels and light gun shooters. The reason is mostly logistic: I have a limited capacity to buy and play games and so I need to contain my research in some way to make the project feasible. When I look at the number of PC horror games that have ever been made, and the lengthy steps required to purchase and run these games, it is an easy decision to avoid them purely on cost/benefit grounds. The same can be said for visual novels: the form is slow, there are a ton of them, and I don’t expect to learn a whole lot about how horror games can be made by reading text set against static images (even when the text is really good!).

these clues are designed to mislead the player into thinking they understand the story so that a late scene can pull the rug out from under them when the “true horror” is revealed. Remember, the goal is to keep the player from becoming comfortable.

these clues are designed to mislead the player into thinking they understand the story so that a late scene can pull the rug out from under them when the “true horror” is revealed. Remember, the goal is to keep the player from becoming comfortable.

I had heard something about a new Alan Wake game, released as a short XBLA downloadable title, way back in February of this year. I jotted the game down in my mental list of titles to look up later and then promptly forgot about it. The game came and went without much of a murmur, obscure to even to the collective consciousness of my twitter feed.

I had heard something about a new Alan Wake game, released as a short XBLA downloadable title, way back in February of this year. I jotted the game down in my mental list of titles to look up later and then promptly forgot about it. The game came and went without much of a murmur, obscure to even to the collective consciousness of my twitter feed.