Also known as: Red Seeds Profile

Platforms: Xbox360, PS3

Release Date: 2010-02-23

Regions: USA Japan Europe

Chris’s Rating: ★★★★

This fascinating translation of Twin Peaks to game form isn’t harmed by a few rough edges.

What follows is a long article about Deadly Premonition. I originally posed this as four separate posts on the front page, but here I’ve collected all four posts into a single document. This is tl;dr territory.

This isn’t really a review as much as a stream of consciousness; the game pushes a lot of buttons and rather than trying to enumerate them all, I think I’ll just meditate on the game a bit. That seems like the correct way to approach this particular game.

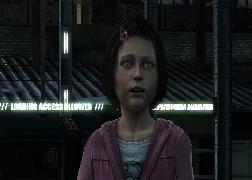

Before I get started, let me give a short mini-review for folks who don’t care what games mean. Deadly Premonition is Twin Peaks, in game form, as seen through Japanese eyes. Though wacky, it’s fairly low-tech; some of the mechanics are extremely rough, the game play systems feel at least a generation old, and it’s not going to win any awards for prettiness. But what Deadly Premonition lacks in technical polish it more than makes up for in storytelling, characters, and most importantly, its integration of game design and visual presentation. It’s worth playing for any of those pieces, and in combination the game is fascinating. Deadly Premonition is to Resident Evil 5 what Tetsuo the Iron Man is to Terminator 2. If you have any interest in games that experiment with story telling and mechanics, Deadly Premonition is more than worth your time.

THE UNCANNY

The internet, particularly one specific blog about games, has made a big deal out of the ridiculousness of Deadly Premonition. The music doesn’t match the scenes, the characters and dialog are often nonsensical, and the whole thing has a decidedly strange sense of humor. It’s very easy to write this strangeness off as normal “Japanese insanity,” and in truth, there are a few aspects of the game that seem strange because of culture clash. But I think that chalking Deadly Premonition’s strangeness up to the cultural divide is a vast oversimplification; classifying it as weird just because it came from a foreign country does the game, and its designers, a disservice. Deadly Premonition is weird, but the odd, off-beat rhythm that it follows–something Freud calls ‘the uncanny’— is entirely intentional.

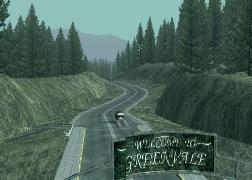

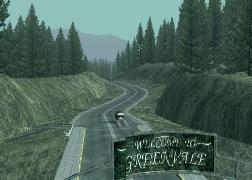

The way to think about Deadly Premonition is to consider it the game version of Twin Peaks, the fantastic TV show by David Lynch and Mark Frost. I went back and watched Twin Peaks while playing Deadly Premonition, and the similarities are unarguable; some characters and scenes have been directly lifted from the seminal show for use in this game. At one point I was having trouble remembering which events were unique to the game and which had occurred in the show’s plot as well. Replace the Log Lady with the Pot Lady, substitute the town of Greenvale for Twin Peaks itself, and insert Agent Francis ‘York’ Morgan in the role of Agent Dale Cooper, and you have created Deadly Premonition out of Twin Peaks. To say that one is influenced by the other is an understatement; though the stories do branch and change, for most intents and purposes, Deadly Premonition is Twin Peaks. The game even opens after each reload with a video summarizing recent events, mimicking the way Twin Peaks and other shows open with a short summary of the previous episode.

Both Twin Peaks and Deadly Premonition star FBI agents who use unconventional means to locate their suspects. Agent Cooper throws rocks at a milk bottle while Agent York goes fishing for missing files. They both have a love of food, particularly coffee, and they both speak with a timbre that we, and the other characters in the game, find strange. Both are visiting rural American towns from the big city, both are investigating the murder of a young woman with a double life, and both are outsiders. They both use dreams to guide them, and find significance in bits of evidence that appears inconsequential to the police. Agent Cooper notices a picture of a suspect on a particular magazine page and Agent York gathers clues by reading words out of his morning coffee.

It is within this context that Deadly Premonition must be understood. The game is not a carbon copy of Twin Peaks, but it’s a very close relative, like The Magnificent Seven is to Seven Samurai.

And within the context of Twin Peaks, Deadly Premonition’s strangeness doesn’t seem so out of place. Twin Peaks itself is very strange; there is much that goes unexplained, so many scenes that leave the viewer feeling more confused than ever. This is, after all, a production involving David Lynch, a director who’s never been particularly interested in handing the answers to his audience on a silver platter. No, the strangeness in Deadly Premonition is mostly intentional, as it is in Twin Peaks. Agent York sort of acts like a lunatic because that’s the sort of personality required to resolve the mystery with which he is tasked. Agent Cooper is able to track his ghostly killer because he is able to follow a path that leads away from the rational world and yet eventually arrives at the correct result. Deadly Premonition may be strange, but it’s strange for a reason, and that reason has a lot more to do with its story than just being from Japan.

That said, the sort of unbalanced, off-kilter, uncanny feeling that Deadly Premonition promotes is indeed at least partially the result of culture shock. As I’ve written here many times before, culture shock is an asset to horror because it makes us feel like we’ve lost control. Deadly Premonition does this intentionally as well, but as with many other Japanese games, its very foreignness helps it scare us. The town of Greenvale itself is perhaps the most obvious example of this effect. The town looks like a rural American town in the Pacific Northwest; it has been painstakingly reproduced in digital form by the developers, who visited parts of Oregon and Washington to do location research during Deadly Premonition’s development. As diligently as it’s been recreated, Greenvale feels, to my American eyes (and as somebody who grew up in Oregon), a little like something out of The Twilight Zone. It reminds me of Santa Destroy from No More Heros, another game by Japanese developers that attempts to recreate an American town (though that one appears to be in Southern California). Little things here and there are wrong; for example, not only does each street in Greenvale have a name, the street names change every block. Most streets in Japan do not have names, so perhaps the designers at Access Games misunderstood how street names are used in the US. Or perhaps it was intentional. So much is intentionally odd in this game that it’s hard to tell. Whatever the rationale, the result is that Deadly Premonition can be more engaging and upsetting than it has any right to be.

THREE KEY SUCCESSES

The August 2010 issue of Game Developer magazine has a lengthy post-mortem review of Deadly Premonition, written by SWERY (the game’s director) and several other staff of Access Games. The developers select five areas in which they feel Deadly Premonition was most successful: character building, story and world building, distinctive music, casting and voiceover work, and the team’s hardcore passion for the title. I think this is an extremely honest review (the “what went wrong” section is all about the technical aspects of the game that didn’t work out very well, which I mentioned at the start), and I agree with the developer’s selections. In particular, I think that they have hit the nail on the head by naming characters, story and world, and music as the three most important elements of Deadly Premonition.

Deadly Premonition is a mystery, and it revolves around its characters. The central character, Agent York, is highly eccentric; his eccentricity makes him a fun character to play, and gives the story a reason to exist. His approach is unwaveringly serious, whether he is describing the mechanics of the relationship between Tom and Jerry (yes, the cartoon) or inspecting the teeth of a corpse. He’s constantly smoking, something we rarely see in heros today, but for York smoking is a kind of meditation.

One of the key elements of this game that propels it to such absolute quality is the way that York’s character is delivered to the player in the game. York talks to himself constantly, and these conversations serve to reveal much depth in his personality. Even better, the conversations appear to be with the player himself; York addresses you, the person holding the controller, in a way that few games have ever attempted (Metal Gear Solid 2 is the only somewhat similar title that I can think of). These moments of dialog are fantastic, but I particularly enjoyed the discussions York has with Zach (the name he uses to address the player, and eventually an important character himself) while driving. Greenvale is a large area, spread out over a five mile region, and it takes a while to drive around. While in the car, York speaks to the player about his past, his relationships with other characters, and old movies. Few games, let alone open world games, are able to work this much dialog in without stopping for cutscenes; according to the developers, York has over 3000 lines of dialog in Deadly Premonition, accounting for half of the total dialog in the game. Other games have used dialog this way before: Bioshock used reams of dialog to teach the player about key characters and the surrounding world, and Silent Hill 3’s world descriptions are all written in Heather’s voice, teaching us much about her personality. But Deadly Premonition does it better than those games. By the end of the game we feel not only great empathy for York and some of the other characters, but also that we understand his eccentric personality.

I also enjoyed the story in Deadly Premonition. Unlike another game I played recently, Deadly Premonition kept me guessing as to the real identity of the Raincoat Killer (though I did suss another, more important antagonist very early in the game). The story is interesting, and well told. It revolves around Agent York himself, and becomes intensely personal in its final act. It’s a fairly complicated tale, and one that requires a few stretches of the imagination, but it’s pretty interesting. And that’s the point.

The third success named by the developers is music, and I wholeheartedly agree. The soundtrack for Deadly Premonition goes with its content very well. Remembering that this game is directly descended from Twin Peaks, there are a few tracks that are clearly designed to fill the same ominous-yet-strangely-uplifting role that is filled by that show’s main title theme. There’s a lot of acoustic guitar, piano, jazz sax, and humming in the musical landscape–not what you might expect from a horror game. My favorite track has to be the Red Tree theme, which includes a “lunatic improvisational section” to describe the madness that grips the Raincoat Killer’s subconscious. It fits right into freaky Red Rooms, angel twins, old men in wheelchairs and gas masks, and all of the other uncanny imagery that the game throws at you.

PROBLEMS, REAL AND IMAGINED

Most of the technical issues with Deadly Premonition are not true problems, just systems that seem to be too simple compared to the modern state of the art. The textures and animation, for example, are pretty low quality. The aiming system is unwieldy, and for some infuriating reason the targeting reticle vanishes once you start to fire. The collision detection is pretty strict and angular. The movement of the enemies makes for challenging gameplay until a certain weapon is acquired, after which the combat is trivially easy (with the exception of one truly annoying enemy that took me five minutes to kill each time). The camera seems jumpy because it always aligns itself with the angle of the floor. These are the sorts of technical issues that crop up in Deadly Premonition; not really bugs so much as areas lacking in the polish we’ve come to expect from modern games. There’s nothing here that really gets in the way of the game play either–no fatal flaws or deal-breaking mechanics. Just technical roughness.

There is, however, a real problem that is worth mentioning. Deadly Premonition swings wildly between closed-off linear game play modes and open world, free form modes. Both are interesting in their own right, but the free form mode in particular has a lot of fascinating features, specifically, the way it manages time. The town of Greenvale is tied to a clock that controls when stores open, how characters move around, when the sun rises and sets, and there’s a huge amount of content here. You can sneak up to a character’s house and look in the window to see what they are up to at any given time. If they are home, they’ll be moving around, doing chores or watching TV. The town feels alive.

But the progression between these two modes is unpredictable. Most of the game is fixed and linear (though sometimes occurring within the open world), but at a few points the player finds himself with no immediate goal and is free to explore. The timing and frequency of these undirected sections is off. The first open world segment appears early in the game, before the player has had a change to grasp how the whole time-of-day system works yet. The player must be at a certain location at a certain time, and indeed, can choose to simply sleep in the hotel until that time approaches if they wish. I think most players are excited to get out and drive around.

Only, there’s not much to do at first; many of the shops open at odd times, and time in the open world mode progresses extremely slowly. Shenmue had a similar system and users complained enough that in Shenmue 2 they added a way for the player to accelerate time while they wait for a specific appointment. This first open world section seems to go on forever–I spent several hours of play driving around the city, running errands, finding items, and talking to characters. There are a few side missions that you can accomplish, but there’s no way to get anywhere close to beating all of them in this early section. Instead, the mode seems to drag on until finally, thankfully, the meeting time approaches and you can get on with the story. And as it turns out, that moment is the only time in the game where the player is given such freedom; every other open world segment is tied to a specific goal, or a short time limit. After spending so much time in the open world mode, I wasn’t excited to go back to it–I wanted to see the story progress, find the killer of the beautiful young girl. When I had a chance to do open world stuff again, I instead opted to beeline for the next obvious goal so that i could see what was going to happen next. Nothing forced me to do this, but since everything is tied to a clock, missing the next deadline would mean a whole ‘nother 24 hour cycle in the open world. That didn’t seem acceptable to me–I was hot on the trail of a serial killer and goddamn it, I’m going to catch him. There was just no time to waste.

I think that the long initial open world section, combined with the subsequent velocity of the plot, sucks a lot of the life out of Deadly Premonition’s dual mode design. I probably only experienced 1/5th of the total content available in the game (though it still took me close to 25 hours to complete) because I was more interested in advancing the story than driving around completing side missions. Perhaps that was the goal–to allow me to select the type of game play mode that I prefer–but it was still annoying.

But that’s the only real complaint I have with Deadly Premonition. The technical flaws were not a problem for me (though I do have a bone or two to pick with the aiming system and instant-failure quick timer events), and the rest of the content was so good that other minor flaws are easy to forgive. And really, when discussing the mechanical parts of the game design, Deadly Premonition gets much more right than it gets wrong.

THE OTHERWORLD

I really like how Deadly Premonition deals with the Otherworld, a label I am borrowing from the Silent Hill series to describe an alternate reality, infested with zombies and other malicious creatures, that mimics the look and layout of the real world but seems decrepit and decayed. In Silent Hill, the Otherworld is often a form of narrative beat, a way for the characters to pass into a yet-scarier version of the game, a way for the designers to ratchet the tension up another notch (or, in some cases, two or three notches, all at once). Deadly Premonition uses the same sort of game mode a different way: to separate straightforward reality from the world of hidden connections and meaning. Agent York’s descent into each Otherworld is more like a descent into the unconscious mind, where he’s able to find links between things that are not obvious in the real world. This is how York performs his investigation, by finding bits and pieces of seemingly unrelated clues and then linking them together in a way that makes the picture clear. He does this in his dreams, and sometimes the middle of a normal day. But in the Otherworld, York has the ability to physically explore this space. He calls the method “profiling.”

The Otherworld is not a safe place, however. Though York is able to use this nether region to draw conclusions from uncommon sources, he also makes himself vulnerable to the malicious entities that reside in that space. Perhaps, if we see the Otherworld strictly as York’s unconscious mind, we might conclude that these entities are of his own creation, based on what he knows about the case. I think it’s more likely that York is visiting a physical space, a sort of distorted mirror of the real world, where evil takes a different, more substantialform. This interpretation is reinforced late in the game, when other characters enter the Otherworld as well.

In terms of pure game mechanics, the Otherworld gives the designers a way to cleanly break between the open world and a more traditional indoor level design. This is a great place for zombies, gun combat, and exploration, which are all hard to do in an open world setting. The decision to switch not only game modes but also thematic modes when entering the Otherworld is, I think, pretty smart.

Deadly Premonition also uses the Otherworld to do something that is rare in video games: subtle foreshadowing. The game is the best example of foreshadowing that I’ve seen in quite a long time. One of the genius parts of Deadly Premonition is its use of color; the palette of the game slowly changes as Agent York gets deeper and deeper into the Otherworld, until finally the game simply smears a bright red haze over the entire frame. Silent Hill 2 used color to foreshadow, as did Condemned. But there are very, very few games that can make such a claim, and Deadly Premonition does it very well. Foreshadowing extends to level geometry as well; there’s a particular section near the end of the game in which the player must climb an incredibly long staircase (sort of the reverse of Silent Hill 2 and 4’s impossibly long staircases), all while very specific, crazy music plays in the background. The effect is pretty dramatic; the level of tension as the player reaches the door at the top of the stairs is very high.

FINISH IT UP, ZACH

This has been a long, unorganized stream of consciousness about a weird, delightful, scary game. If you couldn’t tell, there’s a lot of food for thought in Deadly Premonition, which I think is a mark of high quality. Though many reviewers may have been turned off by a lack of superficial polish, I think that Deadly Premonition is one of the best games I’ve played in a long time. It’s absolutely worth playing, thinking about, investigating, and examining. It is a rare gem.