Note: This article was originally published in Well Played 3.0 in 2011. I wrote about the book here at the time, but the old links are dead and these days you actually have to buy the book or go wading through academic PDF sites if you want to read it. So I am reposting it here. Obviously a lot of new horror games have shipped since I wrote this, but I think Siren is still one of the top contenders for this accolade.

In 2003 I decided to become an expert on horror games. At the end of the previous year my wife and I had moved from icy Albany, New York, where I was employed as a game programmer, to sunny Stanford, California. My employers were nice enough to let me continue writing games for them from our new apartment (a tiny cinderblock one-bedroom on the Stanford campus), and my daily routine involved logging in at 7 am, coding in my underwear for several hours, taking a break before lunch to shower, and then going back to the code until supper time. At the time I was the lead engineer on a forgettable Game Boy Advance game based on a forgettable animated movie, and for the first several months my productivity was very high because I had no reason to leave the apartment.

But after a while the routine started to get to me. Physical isolation was part of it; I didn’t know anybody in California, and the only people I talked to were my game team via the Internet. Despite the warm weather I almost never went outside, and I’m sure some form of advanced Vitamin D deficiency contributed to the malaise I found myself in. One day I spent several hours seriously weighing the merits of taking a baseball bat downstairs and trying to locate the one car in the lot that randomly sounded its alarm every few hours. It was time for a change.

So I decided to become an expert on horror games. I started by making a list of titles that I knew about. The first version was an Excel spreadsheet that I printed out and stuck on my bulletin board. It was little more than a glorified shopping list, and it had about seven games on it. As I began to research the genre, I found that there were hundreds of games that could be classified as horror, many on old PC platforms that could no longer be run. Even limiting myself to console games, I quickly uncovered a large number of titles. In typical programmer fashion, I ditched the Excel document and instead wrote a bunch of code to track my growing list of horror games in a real database. The goal, I decided, was to play every game on this list to completion, write up a short review of each title along the way, and hopefully, after sampling a large range of horror games, draw some conclusions about the genre as a whole.

The result was a web site called Chris’ Survival Horror Quest. I put the first versions online in early 2003, and by August of that year it had turned into a sort of blog (although at the time, the word ‘blog’ hadn’t yet entered the vernacular).

One of the very first posts I made was about a new horror game from Sony Computer Entertainment called Siren (Forbidden Siren in Europe). There was no information in the post, just two creepy screenshots of misty locales and kids with bleeding eyes. The game was released in Japan that November, and then in the States in early 2004. I picked it up, played it for a while, and then put it down. The game was frustrating and difficult. I wrote an angry, complaint-filled rant about the game for the blog and then set it aside. A few months later I picked it up again, and this time it clicked. All of a sudden I was hooked.

Completing Siren was hard. It took me months, even with the aid of a hint book full of maps. When I finally finished after half a year of play, I posted to my blog that Siren was the scariest game that I’d played thus far. It’s been six years since then, and I’ve played a whole lot of horror games, but none come close to matching Siren in terms of scariness. At this point I’m willing to call it the Scariest Video Game Ever Made.

I’m not trying to be hyperbolic here. Since I began my quest to understand horror games in 2003, I’ve made it my business to finish every single horror game I can get my hands on. As of this writing I’ve played about fifty horror games through, and there are another fifty sitting on my shelf in various states of completion. If my calculations are correct, this means that, within the genre limitations I’ve set for myself, I’ve tried almost every single game ever produced in the horror genre. I do not mean to brag; actually, my horror game collection and borderline obsessive interest in the genre is a bit embarrassing. But I do feel confident that I have sufficient experience to select the Scariest Video Game Ever Made, and that game is clearly Siren.

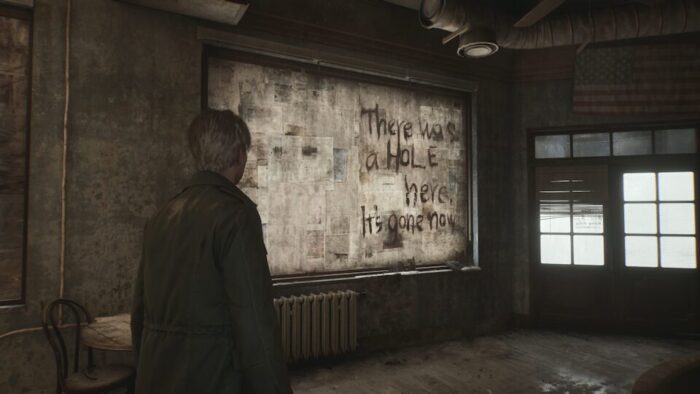

Siren is a third-person horror game. It looks a whole lot like Silent Hill: it takes place in old, dilapidated places, which are often shrouded in darkness or mist, and characters must frequently use a flashlight to navigate. The game even shares some of the original Silent Hill team’s staff. The plot, which is told in out-of-order segments and focuses on a diverse group of playable characters, involves a remote Japanese village in which many of the residents seem to have changed into murderous zombie-like shibito. The central mechanic in Siren is “sight jacking,” the ability to see through the eyes of shibito who are close by, and to survive the player must use it constantly. The graphics are nice and the sound is particularly key to the overall experience. Described this way, as just the sum of its various parts, Siren sounds like a pretty good horror game.

But it’s not a pretty good horror game; it’s not even a great horror game. It’s the Scariest Video Game Ever Made. And to understand why it is the Scariest Game Ever Made, we need to look at how Siren works at a much more fundamental level.

Off the Beaten Path

I have a very clear memory of playing Siren one evening in my concrete apartment, after my wife had gone to bed. I had progressed through a long, complicated level set in an abandoned hospital (a popular locale for horror game designers), and to complete it I needed to cross an open courtyard to some sort of monument placed in the center. The courtyard was unfortunately inhabited by a lone shibito, and low on health and lacking any means to defend myself, I knew that I wouldn’t survive an outright dash for the end. Instead, I searched the outlying area for some sort of weapon or health item. I found a bunch of junk: a burned-out light bulb, a broken TV, and a laundry shoot embedded in the side of a wall.

After some thinking a plan began to form in my mind. I made my way to the second floor and found the top of the laundry shoot. When the roaming shibito was near enough, I dropped the bulb down the shoot. The monster heard the sound of the bulb breaking and changed course to investigate. I waited until he stuck his head into the bottom of the shoot before dropping the TV down the hole. There was a crash as it crushed the shibito’s head in, and, feeling extremely pleased with myself for having figured the sequence out, I leisurely progressed to the end of the level. It was one of those moments where I was more surprised as a player that the puzzle had worked so naturally—though it was clearly a carefully designed encounter, the whole thing felt thrillingly organic. The sweat on my palms was proof enough of that.

Siren is a deeply innovative game. It’s an absolute treasure trove of interesting game mechanics and ideas. Not every idea is successful, but the shear amount of design experimentation found in the title is astounding. In fact, Siren is such a departure from regular gameplay norms that it’s challenging to decide which of its many innovations are the most important.

The key to understanding Siren is that it is, at its core, a stealth game. The stealth genre, defined by designs in which the primary mode of play is sneaking, is dominated by games about ninjas and spies; horror and stealth is not a common combination. In fact, I don’t think that there are any other true horror stealth games outside of the Siren series. Clock Tower and its brethren (including Haunting Ground) are based around running and hiding, but not so much sneaking. Deadly Premonition has a sneaking mode in which the player can hold his breath to hide from enemies, but it is more of an ancillary move than a core game mechanic. In Silent Hill and many other games, it’s possible to avoid combat by turning off your flashlight and moving quietly, but these games rarely reward this behavior; instead, being able to sneak passed an unsuspecting enemy is often used as a way to make the game slightly easier. The only other real sneaking game in the horror genre is Manhunt, and that title is so different than the rest of the genre that it is its own class altogether (though it does share a few key traits with Siren, which we’ll get to). As a stealth horror game, Siren is pretty unique. The stealth design works by throwing the player into large, sometimes open-ended levels, which are populated by various shibito. Siren’s shibito are zombie-like, but unlike traditional zombies they retain some higher-order skills, like shooting guns, using flashlights, and even locking and unlocking doors. Most of them seem to be acting as they did when alive, perhaps out of habit: until they notice you, they’ll tend the fields, or clean the house, or patrol an area (or, later in the game, spend their time building disturbing structures). As in many stealth games, the core game mechanic involves learning the patterns of the enemy and then deftly sneaking passed them when their backs are turned. Since Siren has no mini-map (nor any other sort of on-screen HUD), the only way to actually learn the shibito’s patterns is by using sight-jacking to peer through their eyes. By closely examining what the shibito see, the player can identify blind spots in the map and carefully sneak by.

The key here is that it’s never quite clear what the shibito can hear and see. The range of their perception is fuzzy, and in fact certain shibito have much better senses than others. This is quite a departure from the stealth precedent; most sneaking games follow the Metal Gear Solid approach of explicitly rendering each enemy’s range of vision on the map, and many implement increasing levels of alertness (as defined by Tenchu: Stealth Assassins) in order to give the player a way to retreat if they are about to be discovered. Siren, on the other hand, offers the player neither affordance: it purposefully obfuscates the exact boundaries of shibito perception and its enemies respond aggressively to the slightest motion or sound. In this respect it is similar to Manhunt.

Couple this fuzzy perception model with an extremely unforgiving combat system and you have a highly stress-inducing stealth mechanic. If the player is found by an enemy, it is unlikely that he’ll survive the encounter, and even if he does, the sound made by combat will likely draw other shibito. So the player is forced to move quietly, and slowly, and hide in areas that may or may not be safe. Many times a successful sneak will require the player to cower just a few feet away from a roving shibito, and since it’s never quite clear whether or not a given hiding spot is truly safe, these moments are heart-stopping.

It is normal for game designers to try to limit player stress and frustration by giving them ways to adjust the difficulty: think checkpoints and power-ups. Siren selects the opposite direction and makes its core stealth mechanic extremely high-stakes. It then doubles-down on this approach by layering puzzles on top of the basic sneaking system. The design ensures that the player never has a chance to fall into a comfortable routine, and must constantly be thinking on his toes.

The puzzles in Siren are varied and, occasionally, ingenious. While the rest of the horror genre seems to be mired in fetch quests involving locked doors and key cards, Siren invents whole new classes of puzzles. Many involve distracting shibito from their regular patrol so that the player can pass; in one early puzzle, the player must make a pay phone beep incessantly by inserting an expired phone card so that a nearby shibito leaves his post to investigate the noise. Others involve using the actual environment; late in the game, the player must break through a locked door by timing his strikes against the lock with a thunderclap, thus masking the sound from nearby shibito. Some puzzles involve the level progression itself: a door unlocked by one character may allow another to pass through that same door at a later time.

There are all kinds of other interesting ideas here, and as far as I know, many of them are unique to Siren. The level progression system is presented as a dependency graph-spreadsheet-thing, with time on one axis and characters on the other, so that levels completed at certain times by certain characters unlock other levels at other times with other characters. Many levels have multiple end conditions, and must be played several times to unlock the entire graph. Almost all of the game’s huge cast of characters are playable at some point, but by the end very few survive. Siren represents a huge departure from the norms of both the horror genre and the stealth genre as well.

Culture Shock and Horror Affordances

But just being a highly innovative game probably wouldn’t be enough to name Siren the Scariest Video Game Ever Made. Even the stressful core sneaking mechanic, while quite traumatic on its own, is not sufficient to warrant the Scariest Game title. No, there’s more to Siren than just interesting core mechanics. There’s another aspect to the game that makes it much scarier than other horror games, even games that employ similar design patterns, like Manhunt. I’m going to call that aspect Siren’s “horror affordances.”

In user interface design schools, an “affordance” is something that suggests its use just by the way it looks. The handle on a teapot is designed to look like it would be easy to grip, and thereby saves you from scalding your hand by trying to pick the pot up by its base. The handle “affords” gripping, the UI designers would say. Its design suggests its intended use.

I’m going to use the word in a similar way. A “horror affordance” is something that affords horror; that is, it is some element that makes it easier for you to become scared, or even suggests that the appropriate reaction to the element is fear. Siren is scary because it has several different horror affording elements, and not all of them are obvious.

Siren’s first horror affordance is the stressful sneaking mechanic I discussed above. That’s one element of its assault on your emotional state.

Another horror affordance is the game content itself: the monsters, the characters, the level design, the dialog, the camera work, all of the things that make up the narrative events of the game. The sound design is particularly noteworthy here; hearing the shibito sob and laugh while looking through their eyes is more than a little bit unsettling. To the casual observer, it might seem like the game content is the central horror affordance: it stands to reason that the monsters are scary and the locations are scary and therefore the game is scary. But I think that the scary content is just one more piece of the Siren formula, and not the most important piece at that. Though many games have great content, very few are successfully scary, so content alone cannot explain how Siren works.

I think Siren deftly employs a much lower-level horror affordance: culture shock.

As a sophomore in college I spent a year in Japan on a study abroad program. I ended up getting a degree in Japanese (along with one in Computer Science, though I had to cram my CS classes into three years since my excursion to Japan put programming on hiatus), and as I write this I am sitting in an apartment in Yokohama. But looking back, I realize that my first year in Japan was spent mostly trying not to lose my grip on reality; I was caught in the throes of culture shock.

Culture shock, at least for me, is like trying to stand up on a boat. The floor of the boat itself appears flat, and sometimes the motion of the waves is so subtle that I can’t really even feel it when sitting down. But

when standing up or (god forbid) trying to walk, I’m suddenly off-balance. The random, pattern-less rocking of the boat clashes with my brain’s assumption that flat ground is fundamentally stationary, and consequently I am surprised by even the smallest motion. It’s a weird, stressful sensation that I have lost control; I do not fully grasp the forces acting upon me.

That’s how it felt when I first came to Japan. The juxtaposition of Japanese sensibilities with familiar Western symbols made me feel like the world had gone crazy. Parts of Japan look a lot like an American city (there are tall buildings and nice cars and people wearing suits), but (I eventually realized) the motivations of the people living in Japan are often quite different than those of my culture of origin. Even minor incongruences made me feel uneasy; there were so many new things to absorb, my definition of “common sense” suddenly seemed unreliable. I felt like a fish out of water—the sensation of lost control was very strong.

This feeling of being out of control is a powerful horror affordance. I might go as far as to say that loss of control is a central element in almost all forms of horror; media that sets out to scare is often fundamentally about making its audience feel vulnerable by removing all connections to comfortable routine. Consider horror films such as The Shining, The Birds, and Alien. These films throw their characters into confusing, conflicting, incomprehensible situations, and never really stop to let the viewer catch up. This keeps us off-guard, constantly second-guessing our assumptions. It puts us in a very vulnerable state, and lets the filmmakers pipe their scary content directly into our brains.

Siren achieves this same effect through culture shock. It does this in two distinct ways.

First, it presents to us a weird, disjointed, out-of-order story, in whichcharacters are not clearly good or evil. The effect is amplified for Western players because the story content is rooted in Japanese culture, and the motifs and clichés it employs are decidedly unconventional to our eyes. Siren’s narrative isn’t the first to benefit from its foreignness; I suspect that the recent Asian horror film boom in the United States has more to do with culture shock than filmmaking. But, as with other horror films and games that are distinctly Japanese, Siren’s ability to scare is improved because it seems unpredictable to us; it doesn’t follow the standard, comforting format that we’re used to.

It’s also important to mention that Siren is stock-full of references to Japanese mythology and urban legends. The eventual antagonist, Hisako Yao, is based on a character from Japanese folklore called Yaobikuni, a woman who ate the flesh of a mermaid and became immortal. This folklore is not commonly known in the West, and thus it is a vector for culture shock, a strong horror affordance.

The second form of culture shock that Siren employs is entirely unrelated to its country of origin. Rather, the core mechanics of the game, the sneaking and innovative puzzles, are so far from the norm that they represent a horror affordance themselves. The culture here is modern game design precedent—a set of rules that are so universal that players recognize them as systems rather than game content. When you find a key with a symbol on it in Resident Evil, you know it’s just a matter of time before you also find a locked door with the same symbol engraved above the lock. When you collect an item that has no immediate function, you can usually assume that it’ll end up being combined with other items or used in a specific spot. And any time a tentacle monster appears, its tentacles will have bright glowing bulbous spots which also happen to be particularly weak to gunfire.

This is the Chekhov’s Gun principle applied to game design. Players understand a mechanic and, once they have identified it as a common routine, are comforted that they understand how to play. In fact, rule transparency and predictability is generally seen as a strength by game designers—those games where there’s never really any question about how to play are usually the most fun. Mario’s floating question mark block affords head-butting; if you weren’t supposed to smash it, it wouldn’t be there in the first place.

But Siren presents the player with a different scenario. Chekhov’s gun is hung on the wall in the first scene but revealed to be empty in the second. The puzzles do not follow common patterns, and because individual levels are usually traversed several times by different characters, there’s often no single obvious path to the exit. By refusing to align to the game design precedent, Siren forces its players to think on their feet. Once the player starts to realize that the rule book has been thrown away, anything seems possible. In fact, as in most other games there is usually only a small set of correct solutions to any given problem. But because those solutions are so non-standard, the problem space appears to be extremely wide to the player. Suddenly all of our assumptions about how games are supposed to work seem unreliable and we find ourselves at sea: culture shock.

Siren’s ability to scare us rests primarily on these four horror affordances: tense game mechanics, scary game content, unfamiliar narrative themes, and unconventional puzzles. These elements in combination create an extremely stressful form of play. They also contribute to Siren’s high level of difficulty; since so many elements of the game are intentionally vague or obfuscated, it takes quite a long time for the player to get a handle on how even the most basic mechanics work. I didn’t even really realize that Siren was a sneaking game until I was several hours in, and I think many quit in frustration before they ever really got to the good stuff.

But, as it turns out, that intense level of difficulty is part of Siren’s success, too.

False Emotions and Difficulty Stress

In subsequent Siren games (Siren 2 is a sequel and Siren Blood Curse is a remake), the difficulty level was toned down a bit in response to user complaints. And, for the most part, that change was successful; the game retained much of its scare power without forcing the player to continuously fail in order to learn the basic game mechanics. But, at least to me, the experience wasn’t quite the same. The games were fun and certain sections were still extremely stressful, but I felt that the later games never reached the same intense level of fear as the original. They felt a bit defanged, and looking back, I think that might have something to do with the unforgiving difficulty of the first Siren.

A few years ago I read about an idea from the world of psychology called the Two Factor Theory of Emotion. The theory, at least the part I am interested in, states that your body takes its emotional cues from two sources: your physiological state and your mental label for that state. Many types of emotions can trigger similar physiological states: both fear and arousal, for example, can cause your heart rate to go up and adrenaline to be released. To accurately identify a physical response your body therefore looks to contextual cues for help.

Psychologists have shown that by causing a particular physiological reaction and then introducing unrelated context, false emotions can be generated in test subjects. The brain, when confronted with some contextual stimuli, misreads the body’s physical reaction and synthesizes an emotion. It appears that if you can cause a specific physical reaction in the body with one form of stimuli and then juxtapose some other stimuli to provide the brain with a label, you can get a person to believe that they are physically and emotionally reacting to the second input rather than the first.

What does this have to do with Siren? I think that the high-stakes game play and crushing difficulty are vectors for physical stress in the player. Even absent any horror content, the game play mechanics are enough to elevate the player’s physiological state. Not because the mechanics are intrinsically scary, but because the high cost of failure makes them intense. In fact, I think many other non-horror sneaking games provide a similar level of intensity; the sneak-and-wait game mechanic is a pretty stressful interface for the player. And once the player is stressed and their physiological state elevated, all the game developers have to do is introduce scary content. If the Two Factor Theory of Emotion is correct, some players will misinterpret their body’s state as a result of the horror content rather than the game mechanics, and will believe themselves to be scared of the bleeding eye shibito.

Of course, Siren also employs its other horror affordances to increase stress and deepen the effect of its scary content. It knocks down our defenses with unconventional mechanics and content, and keeps its game rules fuzzy and flexible. Many games have zombies, and bleeding eyes or not, Siren’s shibito are not all that unique on their own. They work, I think, because the player is forced into a state in which he’s extremely susceptible to stress, and perhaps is even ready to believe that such stress is a direct result of the mostly-dead villager trying to cut his character’s neck with a scythe. Siren’s horror game content is directly empowered by its difficulty, mechanics, and core game design.

But is it any Fun?

Siren is far from a perfect game. Though sometimes improving its ability to scare, the game’s poorly-communicated mechanics and a couple of major UI blunders (the rotating map and investigate key come to mind) turned many players off. Siren asks quite a lot of its players; seeing the game through to the end is no small feat. But as interactive horror, I think that it is significantly more successful than most other games in the genre. Its combination of mechanics, narrative, and difficulty, as delivered to the player in obscure and unconventional ways, make it the best example I’ve seen of fear-inducing game design.

Sitting in my little apartment, trying to keep my heart from jumping up into my throat, I played Siren to completion. Though it was one of the first titles I finished in my quest to play all horror games, it set a bar which has yet to be surpassed. It is the game to which all subsequent games are compared. While a few have come close to Siren’s brilliance, the vast majority of horror games can’t hold a candle in a haunted mansion to it. And that is why I feel absolutely confident in my selection of Siren as The Scariest Video Game Ever Made.

Deadly Premonition 2 – I am, of course, a big fan of SWERY’s games, and of Deadly Premonition in particular. The decade-later sequel got hammered in reviews for frame rate and technical problems, just its predecessor was criticized for janky movement and low texture quality. In both cases, I think such assessments miss the forest for the trees. The reason to play a SWERY game is to unlock access to SWERY characters that make up the narrative, and DP2’s character roster is in excellent form. My initial take was that Deadly Premonition 2 was to True Detective as Deadly Premonition was to Twin Peaks, but now I think that it has more to do with Lost Highway: everybody lives two (or more!) lives.

Deadly Premonition 2 – I am, of course, a big fan of SWERY’s games, and of Deadly Premonition in particular. The decade-later sequel got hammered in reviews for frame rate and technical problems, just its predecessor was criticized for janky movement and low texture quality. In both cases, I think such assessments miss the forest for the trees. The reason to play a SWERY game is to unlock access to SWERY characters that make up the narrative, and DP2’s character roster is in excellent form. My initial take was that Deadly Premonition 2 was to True Detective as Deadly Premonition was to Twin Peaks, but now I think that it has more to do with Lost Highway: everybody lives two (or more!) lives.