I don’t know what’s going on here, but I think it’s from Japan.

The West has been awash in Japanese popular culture every since manga and anime began to take root with young people in the early 1990s. Within a decade, the import of Japanese media has gone from a tiny niche market to a full-blown pop culture phenomenon. Japanese comics are now available in translation at major bookstore chains, Hollywood is remaking Japanese films like mad (such as Shall We Dance, remade in 2004 based on the 1996 Japanese movie), and some networks are devoting their prime time slots to animation from the Far East. The appeal of Japanese media has taken root in Western culture and has turned into a thriving import industry.

However, Western audiences often experience long-distance culture shock when faced with media created by the Japanese for the Japanese. Despite efforts to tailor Japanese works for the American market, we are often confronted with cultural signals that are uniquely Japanese and have no direct equivalent Western culture. This has lead to a lot of head-scratching on this side of the Pacific, and has given rise to the internet stereotype that the Japanese must be insane. This incomprehensibility has kept some forms of Japanese pop culture from gaining traction with with mainstream Western audiences.

An exception is Japanese horror, which has done particularly well in the West. Movies like The Ring (1998) and Juon (2003) have struck a chord with Western audiences, and have sparked a renewed interest in foreign movies and horror in general. Japanese literature like Haruki Murakami’s The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle is starting to gain a solid readership in the West (though still only a very select group of authors are available in translation), and horrific video games of Japanese origin such as Silent Hill, Fatal Frame, and Resident Evil are consistently popular. It seems that Japanese horror has successfully avoided the mire of culture clash and has made a significant impact on mainstream Western society.

So what is it about Japanese horror that we find so attractive? What has kept it comprehensible and accessible to mainstream Western audiences? What is with all the freaky women wearing white with their hair covering their face? In this article, I will attempt to explain how Japanese horror works within the context of Japanese culture and how this approach is differs from the type of horror that Americans are used to.

Laying the Groundwork

Before we get into how Japanese horror works and why we find it so affecting, I need to define a couple of example tales that I will refer to over and over again in this article. I have selected these stories because I think that they represent a fairly wide spectrum of Japanese horror, not because they are particularly unique to Japan; though I will eventually compare and contrast Western and Japanese horror, this initial treatment is designed to give you some idea of what the cultural landscape of Japan is like when it comes to scary stories. Please note that I am trying to present a general overview of Japanese horror, and consequently this article is full of generalizations; not all horror media from Japan will fit the characteristics that I describe, nor should you consider this article the definitive work on Japanese horror.

The stories I have selected are as follows: The Ring (1998 film version), Toire No Hanako, Banchou Sarayashiki, and Yuki-Onna. Note that the next few paragraphs contain major spoilers, especially for The Ring. If you haven’t seen The Ring yet, do yourself a favor and go watch it right now. If you are familiar with these stories, you can skip this part and jump right to the next section.

-

Sadako crawls out of the TV in The RingThe Ring (リング) is a 1998 film that was directed by Hideo Nakata and based on a novel by Koji Suzuki. The film was released in America under the terrible name Ringu because some marketing executive decided that the remake-starring-white-people took precedence over the Ring name. In The Ring (I am always referring to the original version, not the remake), a news reporter named Asakawa (played by Nanako Matsushima) stumbles upon the story of a cursed video tape while collecting information for an article on urban legends. According to the rumor, a video tape exists that will kill the viewer seven days after it is watched. The only escape from the curse is to make a copy of the tape and show it to someone else, who must then copy it and show it again to save themselves. Asakawa tracks the tape down and watches it only to realize that the curse is real and that she has seven days to live. She spends the rest of the film searching for the force behind the tape, a psychic girl named Sadako who was killed by her father and dumped in a well years ago. As we see at the end of the film, Sadako climbs out of her well and through the TV of her next victim, manifesting her wrath in the physical realm from beyond the grave.

- Toire No Hanakosan (トイレの花子さん, “Hanako-in-the-Toilet”) is another contemporary macabre tale. The story behind Hanako-in-the-Toilet is this: if you knock three times on a particular stall in a particular school’s girl’s bathroom while calling Hanako’s name, you will hear her reply from within the empty stall. This story appeared in the early 1980s and enjoyed wide popularity among school children, spawning numerous books and a few films. Different versions of the tale describe various reasons that Hanako’s ghost sticks around (in some versions she was murdered in the bathroom; in others, she was a girl who committed suicide in one of the stalls), and her response differs widely as well. But the main crux of the Hanako-in-the-Toilet tale is the bathroom stall mechanic: by knocking on a particular stall and calling Hanako in a particular way, you can get her to answer you.

- Banchou Sarayashiki (番町皿屋敷, “The Story of Okiku”) is a classic Japanese ghost story about a maid named Okiku who is falsely accused of breaking a ceramic plate. The dish is part of a collection of ten plates, and is extremely valuable to her employers, a samurai family. Enraged by her mistake, the samurai kills Okiku and throws her in an old well. Every night thereafter, Okiku’s ghost rises from the well, counts to nine, and then breaks into sobs. Eventually her presence is so maddening that the samurai goes insane.

- Yuki-Onna (雪女, “The Snow Woman”) is another Japanese classic. In this story, a young man and his mentor are caught in a terrible blizzard while collecting firewood in a forest. They take refuge in a small hut and decide to stay there for the night. In the middle of the night, the young man wakes up to find a strange woman dressed entirely in white standing over the older man, blowing her breath upon him. The woman turns to the young man and tells him that she had intended to kill him along with his mentor, but because he is such a hansom lad she has decided to let him live. However, she tells him never to speak of this event to anybody, or she will kill him. The man is saved the following morning but tells nobody about his encounter with the snow woman. The following year, the man meets and marries a beautiful girl. They live happily and have several children. Then one evening the man relates his encounter with the snow woman to his wife. In a rage, his wife reveals that she is in-fact the snow woman he met, and were it not for their children she would kill him on the spot. With that, she melts away into the wind.

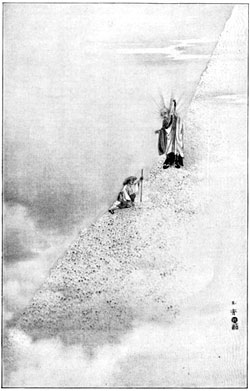

A priest makes a startling discovery in Fragment

Belief Systems

It would not be difficult to write an entire book about the cultural origins of Japanese ghosts, but for the purposes of this article I will try to keep this section short. The two main religions of Japan are Buddhism and Shinto. Buddhism was brought by Korean scholars to Japan from China around 500 AD, but Shinto is indigenous to the country. Interestingly, most Japanese people today practice both Shinto and Buddhism depending on the circumstance; for example, weddings are often Shinto, while funerals are typically Buddhist. Neither religion requires strict membership, and for most people, religious rituals are performed because they are traditional, not because they imply some strong religious alignment.

Thanks to this religious flexibility, Japanese culture has a wealth of legends and beliefs to draw upon from two different religions. Buddhism teaches that life is a facade and that the never-ending cycle of death and rebirth can only be avoided by convincing oneself of this deception. Many Buddhist ghost stories are designed to reinforce that idea (see Lafcadio Hearn’s translation of Fragment[1], in which a Buddhist monk climbs a mountain only to find that it is comprised entirely of the bones of his former lives). Shinto, on the other hand, teaches that any dead person can be prayed to, and otherwise has very little to say about life after death[2]. The Shinto creation myth[3] describes Yomi (黄泉), the land of the dead, but with the introduction of Buddhism Yomi was adapted to fit the Buddhist concept of multiple hells. In practice, Shinto teachings rarely deal with death directly, and only suggest that each person has a soul (called a reikon; 霊魂) that can become stuck among the living if the person dies while feeling burdened with excess emotion or is not given a proper funeral.

This concept of “excess emotion” is something we will come back to, as it provides the underpinnings for most contemporary Japanese horror. The most important point here is that the Japanese typically do not align themselves rigidly to either Buddhism or Shinto, and the reconciliation of these two religions requires the society to accept that most of the universe is fundamentally beyond human understanding. Thus there is a level of ambiguity among beliefs that gives horror a strong basis to operate upon. But I am getting ahead of myself; before we can compare Japanese horror with Western horror, we need to know a little bit more about what we are dealing with. Rest assured that we will return to these points in a bit.

Classic Apparitions and Monsters

Otherworldly Japanese creatures can be broken down into two categories: youkai (妖怪) and yuurei (幽霊)[4].

A tanuki. Yes, those are his testicles.

Youkai are weird beings that are as often bizarre as they are scary. Typically physical (as opposed to the more ethereal yuurei), youkai are similar to Western monsters: they are animal-like and often dim-witted, and though they may be malicious they seldom maintain any long-term goals or plan. This class of monsters includes goblins and ogres and the like, as well as neutral or benevolent creatures such as the tanuki (a shape-shifting prankster that looks like a large raccoon) and tsuchinoko (a snake-like creature that is wide around the center and can jump long distances). There are a great many types of youkai, and they pop up all over the place in Japanese cartoons and comics[5]. However, these creatures are generally not very scary, and they have yet to make much of an impact in the West outside of video games (e.g. Mario’s raccoon suit is in fact a tanuki suit) and comics, where they are seldom depicted as fearsome creatures.

Yuurei, on the other hand, are the heart of Japanese horror. Yuurei are ghosts or spirits that have been stranded on this world because they have some unfinished business or because they died while in the throes of intense emotion. Unlike youkai, yuurei have a singular purpose or mission, and they are very often malicious. A person who becomes a ghost is said to forget everything else about their life and focus only on that which is preventing them from resting. There are scores of stories[6] (like The Story of Okiku) that depict ghosts who come back to haunt their murderers, or to express the anguish that lead to their suicide, or to reward those who fulfill their dying wish.

The underlying concept behind Japanese yuurei is onnen (怨念), the idea that some emotions are so strong that their power can extend from beyond the grave. Almost all classic and contemporary ghost stories from Japan operate on onnen: in addition to the obvious case of Okiku, witness Sadako’s character in The Ring, the antagonist in Juon, or even the explanations given for Hanako’s origin in the Hanako-in-the-Toilet story. Onnen is the central concept behind yuurei, and as we will see, it differentiates Japanese horror from works in the West pretty dramatically.

The Japanese often portray yuurei as people dressed in white funeral garb with long dark hair. Originally, yuurei were portrayed in art and theater as indistinguishable from regular people, but in the 18th century the style changed: since then, the legs of ghosts seem to fade into thin air[7], and they are often shown to have their arms outstretched and hands limp. For some reason, yuurei seem to very frequently female. Perhaps this is because women are thought to hold grudges longer and more powerfully than men.

Japanese yuurei tend to haunt a specific person or place. Since yuurei have an explicit reason for sticking around in the mortal plane, they do not often waste their time attacking people who have no relationship to them. In The Story of Okiku, for example, Okiku’s despair over her false accusation is so great that she is unable to rest, even though she was not at fault. Though her appearance eventually causes her murderer to take his own life, her behavior as a ghost indicates that it was this mistake, not her murder, that brings her up the well every night. We can thus assume that the death of her killer does not put her to rest; she might instead be appeased if the plate were replaced, or if a set of ten plates were placed by her well, thus correcting a problem for which she has been blamed.

This example also reveals another interesting mechanic used in many Japanese ghost stories: the idea that the troubles of spirits can be solved using an effigy or proxy. In Of a Mirror and a Bell (see [6]), a woman kills herself after being publicly humiliated during the construction of a brass bell. In her suicide note, she declares that any person who is able to break the bell by ringing it will be generously rewarded. When the bell is lost, an enterprising farmer is able to conjure up the ghost of the deceased woman by destroying a model of the bell made of mud. This mechanic reenforces the idea that Japanese spirits have a singular purpose in the human world, and that they need not always be malicious to achieve their goals.

Other Characteristics

There are a few other important characteristics of Japanese horror that we should cover before we move on. I discussed the mutability of Japanese religious beliefs above, and suggested that reconciling Shinto and Buddhist beliefs has required the Japanese to accept a level of ambiguity when it comes to explaining the universe. This leads us to our first major characteristic of Japanese horror:

Sarayashiki Okiku No Rei (“Okiku’s Ghost at the Dish Mansion”), 1890 by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi. Notice that her lower body is transparent.

- The universe is governed by rules. This is a central theme in Japanese horror; we can almost always see some sort of logical progression based on some implied set of rules that govern the way all things work. We have already talked about onnen and some of the rules associated with death, but this characteristic implies that there are rules for everything. This often manifests as a sequence of events that must occur before terror can be revealed, such as the Hanako-in-the-Toilet summoning procedure.

- The rules of the universe are beyond human understanding. An equally central theme is that the rules and the reasoning behind them may not be something that people can grasp, and thus one must accept that which he cannot explain. Why does Hanako require a certain stall of a certain bathroom at a certain school to be knocked upon a certain number of times? The answer can never be clear, but that does not stop the audience from believing the story. Another example is the Yuki-Onna story, which suggests that the snow woman has no choice but to reveal herself after her husband betrays his secret; it is as if the promise between them is all that binds her to the mortal plane.

- Modern society offers no protection from spirits and ghosts. Contemporary Japanese horror very often involves ghosts hijacking modern technology, even though the motives of most malicious spirits are not significantly different than they were a few hundred years ago. Perhaps this reflects some anxiety about the amazing speed with which Japan reinvented itself and rose to economic power after World War II. We can see this influence clearly in The Ring (the video tape as a curse), Juon (the characters are constantly confronted by appliances that are no longer trustworthy), and films like Tetsuo The Iron Man, where metal itself plagues the protagonist like a disease.

- Perseverance in the face of utter destruction. It is impossible to talk about modern Japanese culture without acknowledging the impact that the atomic bombs had on the Japanese psyche. A world that has been utterly destroyed and yet must still sustain life is a constantly recurring theme in modern Japanese media: it is a direct theme in works like Godzilla, Akira, and Dragon Head, and it manifests on a much more subtle level in all sorts of other aspects of the culture (consider, for example, Princess Mononoke’s finale).

- Damp Settings. While Western tales of the macabre tend to take place in dry, musty locations such as mansions, basements, or cemeteries, the Japanese tend to associate spirits with water and humidity. Perhaps this is because the Japanese summer months are characterized by intense humidity that persists even after nightfall. The art and culture magazine Kateigaho pointed this characteristic out in an interview with Koji Suzuki, the author of The Ring novel series.

Dank, confined spaces, [Suzuki] believes, are the most conducive to the appearance of ghostly spirits. … It is damp settings rather than dry ones that the Japanese associate with spirits. In Western horror movies, the bathroom is a frequent backdrop to terror. J-horror too makes audiences recoil by suggesting that a disembodied spirit is about to creep into a damp space, a space so damp it’s hard to breathe.[8]

Kateigaho also notes the association of water in some of Suzuki’s works, including Honogurai Mizu no Soko Kara (Dark Water, 2002) and The Ring.

Throughout the remainder of this article I will return to several of these characteristics. A few of them lie slightly outside the scope of this document, but I have included them because I think that they are relevant avenues of study to anybody interested in Japanese horror.

Modern Japanese Horror

Now that we have covered the cultural and historical background for scary Japanese stories, let us take a look at modern Japanese horror within this historical context. With the exception of the above-mentioned influence of technology and the effects of the atomic bombs, Japanese ideas about ghosts and fear have not changed dramatically in the modern era. The introduction of mass communication has certainly brought a great deal of Western influence to the Japanese, but the underpinnings of Japanese horror (such as the concept of onnen) run deep in the culture.

A good case study of classic Japanese horror concepts in a modern package is The Ring. Though there is a wide selection of Japanese horror movies produced before and after The Ring, this film remains significant because it its intense popularity in Japan and abroad. If we closely examine The Ring, we can see that it is in many ways a classic Japanese ghost story retold in modern context. Sadako, the films antagonist, almost perfectly fits the description of classic Japanese ghosts: she wears white, her hair is long and hangs over her face, and she exerts her power in the mortal plane because she died a horrible death. Though Sadako has feet, she’s otherwise very similar to both Okiku and Yuki-Onna. Like Okiku, her remains rest at the bottom of a well, and she must ascend out of the well before she can pursue her revenge. Like Yuki-Onna, Sadako is malicious and destructive, but she is still bound to the rules of the universe. If her victims do not watch her tape, or if they follow the correct procedure to free themselves from the curse, Sadako can have no power over them. The protagonists in The Ring spend most of the movie trying to locate Sadako’s body and put her to rest, but as we see at the end of the film, their efforts are trumped by the rules of the curse. Though the film’s core mechanic requires modern technology (the video tape) to operate, The Ring is very much a classic Japanese ghost story.

Sticking with this theme of traditional Japanese horror in a modern format, let us take a closer look at the Hanako-in-the-Toilet story. On the surface, we can see that it also bears some similarities to The Story of Okiku: the toilet is not all that far removed from an old well, as both are places associated with water, darkness, and filth. This story also adheres to the rules-of-the-universe characteristic, as an exact procedure is required to get Hanako to appear. But what I think is much more interesting about this story is the accessibility of it, especially to school children. As Hiroshi points out on his extremely informative site Gendai Kaidan[9] (現代奇談, “Modern Day Ghost Stories”), the Hanako-in-the-Toilet story is almost perfectly designed to allow school children to test their mettle. The elements required to reproduce the procedure described in the story (i.e. a school with a girls bathroom) are universally accessible, and the consequences of the story are non-threatening (in the original version, correctly calling out to Hanako is supposed to only cause her to verbally respond–there was no implied danger). Hiroshi suggests that the popularity of this story throughout the 1980s was fueled by its simple and easily-reproducible premise, as well as by persistent rumors of classmates who had performed the procedure and actually heard Hanako respond.

The TV is not your friend in Juon.

Both The Ring and the Hanako-in-the-Toilet story tap into the idea that technology and modern society in general provides no protection from spirits. In fact, The Ring and Juon both go a step further and suggest that technology may be exploited by malicious entities to wreak havoc on their victims. This theme is extremely common in modern Japanese horror. One interesting example is the rumor that was popular in the early 1990s during the pager boom. According to rumor, it was possible to get a page from a phone number that could not possibly exist. Even worse, this number (564219) sounds like the words “I am coming to kill you” when read phonetically (ごろくしにいく, “go roku shi ni i ku,” is transformed into 殺しに行く, “koroshi ni iku“).

Another very recent example of this theme is the Flash animation Red Room[10]. Red Room tells the story of mysterious internet popup ad that is rumored to exist. If you surf the web long enough, the rumor explains, eventually you will get a strange popup ad with a nonsensical message accompanied by a weird voice. The rumor holds that if this popup ad is ever closed, you will die. Red Room is a nice example because it embodies so many classic Japanese horror characteristics: in addition to the use of technology by some sort of malicious, otherworldly force, the rules governing the popup ad are both ironclad and difficult to rationalize.

Modern Japanese horror is clearly influenced by the events of the 20th century (especially the second World War, the rise of technology in every day life, and the influence of mass communication), but at its core it remains faithful to the characteristics that have defined Japanese macabre for several hundred years.

West of the Sun

Now that we’ve covered the elements and history of Japanese horror, let us take a look at how the West compares. Europe has a rich history of stories about ghosts and other monsters, and America has happily inherited much of that culture. In his book Danse Macabre[11], Stephen King identifies three archetypical stories that he believes have shaped modern American horror: Frankenstein, Dracula, and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Indeed, the themes in these stories have become so ingrained in American culture that horror (especially horror cinema) has become defined by these clichés. Some American horror clichés have become so accepted that we actually have special terms to describe them, such as final girl[12]. It is perhaps our complacency with these themes that makes horror from other countries interesting; after all, horror cannot be very effective if the viewer has a comfortable idea of the outcome from the get-go.

So let us take a look at how contemporary Japanese horror differs dramatically from American contemporary horror. As an American, I have often been struck by the unconventional presentation of Japanese horror films and games. Over the last thirty years American horror film has become increasingly action-oriented; we are often treated to shoot outs, fights, and scenes of monsters mauling victims. Japanese film, on the other hand, has remained mostly understated, relying primarily on mood and pacing rather than blood and guts to achieve scares. Horror author Koji Suzuki points out that unlike most American horror cinema, many Japanese stories do not end in the destruction of the antagonist.

This understated tone actually helps Japanese horror be more effective, as even the results of the protagonists’ struggle are often ultimately in vain (as in The Ring).

Another common aspect of American horror is our burning need to explain away and rationalize the supernatural events that occur in the story. For example, the original script for Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho did not include the final scene where Norman Bates’ psychosis is hastily explained by a psychologist. The scene was added to quell fears held by the producers that audiences would not understand the film’s finale. Similarly, the American remake of Juon (called The Grudge, released in 2004) added several scenes to explain away the antagonist’s motivations and the way the universe works. Unlike the original Japanese version, very little was left up to the imagination. The American remake of The Ring sported similar features: entire sections about Samara’s (Sadako’s post-localization name) life were added to help explain various details of the plot. Almost all American horror films take pains to explain why events in the plot occur (though there are exceptions; see The Shining and The Birds).

In contrast, Japanese horror literature and cinema usually poses more questions than it answers. Why is Sadako so powerful? Why does she use a video tape to return from the grave? What is her long-term goal? How does the curse in Juon work? Why does Hanako respond from her toilet? How did she get there? In general, the is much left unexplained in Japanese horror, which helps lend it some of its power. As horror screenwriter Lucus Sussman points out, “Japanese horror operates on a much more dreamlike level … this actually works well for horror, because horror is about not being in control.”[14]

This comfortability with leaving some things unexplained may relate to Japan’s religious flexibility. As previously mentioned, reconciling both Buddhism and Shinto within the culture requires the Japanese to accept a level of ambiguity about how the universe works. This is almost diametrically opposed to the classic Christian perspective, which tends to break the world down into “good” and “evil” categories. The idea that the rules of the universe are beyond the scope of human understanding also allows horror authors more leeway in creating their stories because their target audience has less of an expectation that all will be made clear with time. This characteristic in turn often leads to more powerful horror stories, as much is left up to the viewer’s imagination.

There may also be another, secondary trait here; while American horror is often concerned with a decent into the unknown (Jonathan Harker’s trek to Dracula’s castle, the group of teenagers entering the haunted house cliché, the Bates Motel in Psycho, et cetera), Japanese tales often describe the unknown invading the known. Sadako comes out of the TV and directly into the homes of her victims, Hanako’s toilet is not a noteworthy location, and the samurai in The Story of Okiku cannot escape the ghost of Okiku because she refuses to stay in her well. This probably relates back to Suzuki’s conclusion that the Japanese accept a degree of otherworldliness all around them, while Americans like to concentrate our evil spirits in a specific location (witness our oft-employed “Ancient Indian Burial Ground” cliché). The American approach may be another side effect of Christianity’s tendency to separate everything into absolutes (in this case, defining explicit physical boundaries between “evil locations” and “normal locations”), but it also means our horror is often less effective; once a character or location is known to be “good” or “evil,” there is a certain degree of expectation we can rely upon to remove tension from the drama. The more vague and invasive approach often employed in Japanese horror can thus be far more affecting, as we do not have any comfortable story archetype to cling to.

Conclusion

Though we may sometimes be confused by the nuances of media from Japan, the country is home to a wealth of history, tradition, and culture. Japanese horror has piqued the interest of Western audiences with its understated tone and lack of easy answers, but outside of its cultural context even horror can be confounding. In this article I have attempted to explain some of the common mechanics of Japanese horror, as well as the belief systems, history, and modern context within which these mechanics exist. Though I have only scratched the surface of the culture of this complex and interesting country, I hope that this article has given you some insight into how Japanese horror works. The study of culture, even through pulp media such as horror film and games, is an intensely interesting and rewarding activity; I urge anybody interested in horror to spend some quality time with some of the amazing works from Japan. There is much more relevant information that could be covered here, but I will leave future investigation up to you. So curl up with your favorite horror movie, game, or book, and pay close attention; beyond the screams and the blood there is a whole culture hiding.

Footnotes:

1 Lafcadio Hearn. (1971). Fragment. In: In Ghostly Japan. Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing. p3-7.

Read it online.

2 Read more about it on Wikipedia

3 Which is itself pretty interesting. See this Wikipedia article.

4 I am borrowing heavily from Tim Screech’s (what an appropriate name, huh?) excellent article entitled Japanese Ghosts. It was first published in the magazine Mangajin (issue 40), but is now also available online. It is very well written and covers a lot more info than I have here.

5 There is an excellent library of youkai available in English at The Youkai Mura:

6 Try these, all from Lafcadio Hearn’s excellent KWAIDAN: Stories and Studies of Strange Things, now available online for free:

7 Again, Tim Screech’s article has a lot more info than I am including here. See the “ATTRIBUTES OF YUREI” section of his article.

8 Source

9 Gendai Kaidan Note that this site is entirely in Japanese.

10 Wikipedia details Red Room

You can watch Red Room, but it isn’t very interesting if you cannot understand Japanese.

11 Stephen King (1981). Danse Macabre. New York: Everest House. p49.

King has a lot more to say about horror in America that I am totally omitting here. You should read his book.

12 Final Girl refers to the last surviving member of a group of victims in slasher or horror movies. Wikipedia has a nice page about the term

I happened to be in Japan a few weeks ago when Catherine hit the shelves. I didn’t really know what to expect from it, other than it is some sort of sexy, stylized horror puzzle game, or something. Against my better judgement I bought the game for full price. The stylistic rendering and promise of a highly-weird, somehow sex-infused plot were worth the price of admission. Any developer willing to take that much risk deserves a purchase, I figured.

I happened to be in Japan a few weeks ago when Catherine hit the shelves. I didn’t really know what to expect from it, other than it is some sort of sexy, stylized horror puzzle game, or something. Against my better judgement I bought the game for full price. The stylistic rendering and promise of a highly-weird, somehow sex-infused plot were worth the price of admission. Any developer willing to take that much risk deserves a purchase, I figured.

an interesting link in the evolutionary chain between the original Resident Evil tank controls and the more modern systems in use today.

an interesting link in the evolutionary chain between the original Resident Evil tank controls and the more modern systems in use today.