On Monday morning I got up early and washed my face, took a shower, and got ready for work. The night before I didn’t get much sleep. I dropped my daughter off at her preschool at 8:30 and then quickly made my way to work, where I had an appointment with a game designer I really respect: Swery. He was in town for GDC, and wanted to visit the office. We drank some coffee and walked around, and then around 11 we said goodbye and separately made the drive up to San Francisco.

On Monday morning I got up early and washed my face, took a shower, and got ready for work. The night before I didn’t get much sleep. I dropped my daughter off at her preschool at 8:30 and then quickly made my way to work, where I had an appointment with a game designer I really respect: Swery. He was in town for GDC, and wanted to visit the office. We drank some coffee and walked around, and then around 11 we said goodbye and separately made the drive up to San Francisco.

If you’ve ever visited San Francisco before you have probably seen the Moscone Center. It spans an entire block between 3rd and 4th street, and takes up both sides of Howard street, which cuts the building down the center. Though built in the early 80’s, the Center has the feel of one of those weird ’70s office buildings: squat and wide and built of swaths of bare concrete, the building’s low ceilings and dark interior remind me of some sort of secret bunker. It’s a little out of place in the middle of San Francisco, with the Museum of Modern Art on one side and the Yerba Buena Gardens resting on its back. Upon entering the Center one is immediately directed down a long escalator, and the majority of the venue’s floor space is actually located under ground.

I arrived in San Francisco around noon and proceeded directly into the depths of the Moscone. This is where I would spend most of the week going to meetings, attending lectures, and this year, giving a few lectures of my own. GDC is the kind of conference that might lead to vitamin D deficiency, as there’s almost no opportunity to experience natural light (not that it matters much to the pasty-white complexions of the overwhelmingly male audience, a group within I can safely include myself). On the other hand, so much walking is involved that it can’t be too unhealthy.

My first order of business was to give my a lecture, a talk about my indie game Replica Island. That seemed to go well, and drew a couple hundred people. I went to a bunch of meetings, went home, worked on my slides for the second talk (this one a sponsored session about Android compatibility), and was out like a light at 10 PM. GDC was officially in full swing.

I arrived Tuesday morning and ran smack into a long queue of people that extended from some lecture room all the way out into the main Moscone hall. Following the line, I was surprised to find that it terminated at the entrance to my own talk; all these people were waiting to hear about Android, and I was the first to speak to them. After giving my second lecture (using hand-drawn slides which contained, as I discovered to my horror in the midst of a point about managing screen sizes, at least one spelling error), I answered a few questions and then dodged out to my next appointment, noting that the length of the line had not been significantly reduced even though the room had been filled for my talk. The rest of the week was a blur of meetings, punctuated by a few key sessions that I made it a point to attend.

This was, overall, the best GDC I’ve been to in some years. The industry is in the midst of a giant change, and the sessions this year reflected that change. David Cage and Swery both gave outspoken, absolutely convincing lectures on why they had bucked so many industry norms while designing their games. Cage described how the lack of expressive verbs in video games led him to the context-sensitive quick timer-like interface in Heavy Rain. “You can’t tell a story with an interesting character if the only way that character can express himself is with five actions mapped to buttons on a control pad,” he ranted (this reminded me of the way that verbs have decreased in Adventure games over time, which I’ve written about before). He also touched on the difference between asking the player what to do next, and asking him how to actually do this, which is also a favorite gem of mine (Cage called this “Journey vs Mechanics,” which might be a better title than my “cognitive vs mechanical” description). Swery presented seven key game design rules that helped him make Deadly Premonition memorable (GameSetWatch has a nice write up). One point that was interesting to me was the idea that players who mimic normal actions within games will be reminded of the game when they are not playing (which is why York smokes, shaves, sleeps, and changes his clothing). Another was Swery’s command that we use our ideas immediately rather than writing them down and saving them for later. Whatever you think of these guys’ respective games, nobody can accuse them of naiveness; they both have put serious thought into the problems they are attempting to solve.

I also took in an interesting talk about Dead Space 2’s art direction (hint: they thought really hard about it), which made me want to play that game. And Eric Chahi’s retro postmortem of Another World, one of my favorite games of all time, was one of the highlights of the show for me. Sadly I missed several other lectures that I wanted to see: Jordan Mechner talking about the original Prince of Persia, Daisuke “Pixel” Amaya talking about the development of Cave Story, and Matthias Wortch talking about narrative design in Dead Space 2.

Half way through the show my feet began to take their revenge for subjecting them to two weeks of conferences in new shoes (I spent part of February in Barcelona for Mobile World Congress), and now my heels have large gashes in them. I walked a loop between the two Moscone buildings, sometimes at ground level and sometimes through connecting tunnel-like passages, with an occasional excursion to the perpetually deserted Metreon building, over and over again. My work took me to meetings with a wide range of developers, so many that I ran through two boxes of business cards in the first few days.

But even as rushed and busy as I was, I can tell you that this year was a fantastic GDC. The shift from consoles towards new markets, like social games and mobile games, has become so strong that the console developers are beginning to sit up and take notice. Hardware in the mobile sector is improving at a much faster rate than many expected, and it’s unclear if we’ll really need to have dedicated consoles ever again. Game design is changing; the rise of the indie game, as well as the arrival of new audiences pioneered by Nintendo and others has caused developers to step back and reassess their assumptions (Cage even called the industry out for failing to significantly innovate in terms of player expression in thirty years). Change is in the air, and it is exciting. For me personally, this was a rather inspiring week.

Friday evening I ate dinner with Swery and some other Access Games folk. Today I had lunch with Pixel and his producer from Nicalis. Tonight I shall sleep, tomorrow I pack, and then Monday I am off to Japan for a brief vacation. It’s hard not to be excited. 2011 is going to be a good year for video games.

The latest issue of Game Developer magazine has an article I wrote called Pressed By The Dark, which is an expansion of the last two posts here on this site about the Two Factor Theory as it might be applicable to game design. The best part about it is that it’s paired with weirdo, crazy awesome “pixel art” by crazy Russian artist

The latest issue of Game Developer magazine has an article I wrote called Pressed By The Dark, which is an expansion of the last two posts here on this site about the Two Factor Theory as it might be applicable to game design. The best part about it is that it’s paired with weirdo, crazy awesome “pixel art” by crazy Russian artist

explain that arousal, it will look for external context in order to find a label for an emotion to explain change. What Schachter and Singer demonstrated was that by causing an unexpected physiological arousal (by injecting adrenaline), and then pairing the subject with some external emotional context (a confederate that displayed emotion), they could cause test subjects to mistake their body’s reaction as an emotional response. In short, they were able to trick the brain into creating an emotion in a situation where it would not have normally occurred.

explain that arousal, it will look for external context in order to find a label for an emotion to explain change. What Schachter and Singer demonstrated was that by causing an unexpected physiological arousal (by injecting adrenaline), and then pairing the subject with some external emotional context (a confederate that displayed emotion), they could cause test subjects to mistake their body’s reaction as an emotional response. In short, they were able to trick the brain into creating an emotion in a situation where it would not have normally occurred.

My daughter turns three this week, so we celebrated by visiting Tokyo Disneyland (which, like Tokyo Game Show and the Tokyo International Airport, is not actually in Tokyo). The place was packed with families and couples (the latter of which take total control of the park after nightfall), but otherwise strongly resembled my blurry memories of the Disneyland in LA that I visited as a kid. The number of rides that are enjoyable by an almost-three-year-old are a bit limited, and the line for Dumbo rarely fell below 50 minutes, so we visited a random selection of attractions. Most of the rides amounted to a tour of a particular brand, rendered in black light, animatronics, and luminescent paint.

My daughter turns three this week, so we celebrated by visiting Tokyo Disneyland (which, like Tokyo Game Show and the Tokyo International Airport, is not actually in Tokyo). The place was packed with families and couples (the latter of which take total control of the park after nightfall), but otherwise strongly resembled my blurry memories of the Disneyland in LA that I visited as a kid. The number of rides that are enjoyable by an almost-three-year-old are a bit limited, and the line for Dumbo rarely fell below 50 minutes, so we visited a random selection of attractions. Most of the rides amounted to a tour of a particular brand, rendered in black light, animatronics, and luminescent paint.

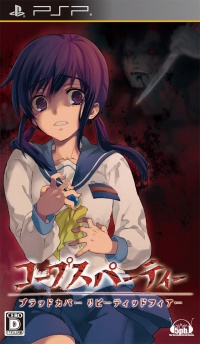

The other day I was in my local BOOKOFF and I ran across a copy of a PSP game called Corpse Party. Actually, the full title per the

The other day I was in my local BOOKOFF and I ran across a copy of a PSP game called Corpse Party. Actually, the full title per the