How can this possibly go wrong?

¥980 is

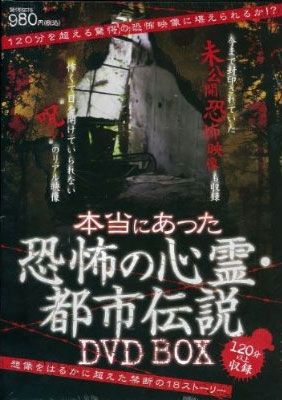

about $10 right now. That is to say, it’s not very much money. It’s particularly cheap for a DVD containing “over 120 minutes of astonishing horror footage.” And yet, that’s exactly what 本当にあった 恐怖の心霊・都市伝説DVD BOX (“Absolutely Real Scary Ghosts and Urban Legends DVD BOX”) offers at that price.

I was more than a little skeptical. I mean, the price point was the first warning sign. The second was that I found this cinematic tour de force in my local Family Mart, of all places, stuffed in-between the weekly women’s magazines and ¥100 onigiri. Family Mart does not sell horror, you know. They’re mostly focused on essentials like potato chips, coke drinks, extra batteries, and umbrellas. A giant box proclaiming to have “real footage so scary you can’t shut your eyes” was a bit conspicuous.

But, I mean, for ¥980, I figured what the hell. Worst (and most likely) case, it’s terrible and I can laugh at it. And maybe, just maybe, there’ll be a gem hiding in those 120 minutes. At 8 yen per minute, you can’t really go wrong. Heck, if I bought this thing off Amazon I’d have to pay for shipping. So I bought it.

This is not the first time I have done this. A couple of years ago I came home with a set of DVDs called Tales of Terror from Tokyo, which sounded terrible and, based on the packaging and box notes, looked like complete schlock. I was pleasantly surprised by Tales of Terror; it turned out that small, 5 minute episodes were a pretty good format and that a couple of the directors involved with the series had produced some pretty neat stuff. I like the idea that a director has a very short amount of time, and probably no budget whatsoever, to find a way to make things scary. Some of the best horror has its roots in simplification by necessity; The Blair-Witch Project is one famous example.

The first hilarious thing about Absolutely Real Scary Ghosts and Urban Legends DVD BOX is that it really is just a box. “DVD BOX” usually means “box set,” here in Japan, but in this case, it’s just a giant, empty box. Well, it’s not entirely empty: there’s some filler cardboard and a single disc. But that’s all. No liner notes, no

There it is in all of its glory. ¥980 well spent.

nothing. At ¥980 these guys are probably making a killing.

The first “story” is a collection of shinrei shashin pictures: photos of regular people in which ghosts are supposed to have been inadvertently captured. The first one is clearly a simple photoshop of the vampire’s face from Nosferatu, and the rest are similarly lame. The sequence of photos ends with the sound of a woman screaming. Not a good start.

Fortunately (and I say “fortunately” because anything is better than watching a video of still photos), the remainder of the DVD contains actual video. The rest of the DVD is a series of “stories” (their word, not mine) about a young woman who ventures into scary, and reportedly haunted, places with her video camera. She carefully climbs a long rock staircase to a supposedly haunted shrine, she ventures into old, abandoned houses looking for certain mirrors that are said to reflect ghosts, and generally freaks herself out. The presentation is more than a little Blair Witch inspired; she keeps a running monologue going and periodically turns the camera to face her (which I found particularly improbable, considering that she’s supposed to be in a scary dark place and the camera is her only source of light). This really is horror on a shoe-string budget.

The thing is, as simple as it is, it almost works. Japan is chock-full of fantastic places to make scary videos like this. It’s got old, moss-covered, dilapidated shrines, there are war-era tunnels and bases to be found, not to mention your standard set of abandoned homes in the middle of nowhere. Even with no budget, the producers of these stories have absolutely fantastic sets to work on because Japan is full of scary-looking places.

But of course it does not work. There are too many basic problems for the scenes to be involving; the reporter woman can’t seem to keep the camera pointed in the way that she is moving so half the footage is a dark view of a floor someplace. And she keeps complaining about how dark it is without once activating the night vision mode on her camera (which the filmmakers make the mistake of introducing to us in the first scene). But the most amazing thing about this series is that nothing actually happens. The reporter ventures into a scary location, gets scared, and then leaves. No ghosts or otherwise scary things ever show up.

And then, and then, as if the producers of this set were on some mission to make the most impotent horror film ever, the series gets even more boring! After the initial reporter has ventured

I’m so scared, I’m filming myself!

into scary-but-ultimately-harmless places several times, a new series starts in which a different girl does mostly the same, but in places that are even less scary (one of the sequences is, I shit you not, about a hill that, according to the DVD, some people think looks like a face). “Oh, I feel something. It’s very sad here. I can feel something like an old man, and he’s very lonely,” the girl drones. Five minutes later the sequence is over and

NOTHING HAS HAPPENED. And then another starts and again,

NOTHING HAPPENS. The last sequence they mix up a bit by having two girls (!!) and a couple of guys venture into some supposedly-cursed area (if people dying in a location is enough to curse it, every square foot of Japan must be cursed), and talk about it for a while, and guess what?

NOTHING FUCKING HAPPENS AND THEY LEAVE!!

This is so far worse, so far, far worse, than I had imagined it could be. At least if they had a guy in a rubber mask I could believe that they were trying. But no, despite the fantastic locales (goddamn face-hill excepted), any potential these sequences might have had for horror is absolutely, completely squandered. They could have made them 10x better without actually spending any more money. Having a guy in a black outfit with a black face mask standing unobtrusively in the corner of one of the scenes, unnoticed by the reporter but obvious to the viewer, would have been enough to push this nonsense into the realm of “potentially watchable.” The reporter people don’t even get properly scared; they just sort of complain about the spot and leave. I mean, come on, I’m going way out on a limb for you guys here. I purchased a video for ¥980. Throw me a bone! Or at least a plastic skeleton! ANYTHING.

I guess that if there is one interesting takeaway from this video, it’s that the filmmakers are obviously working under the impression that their target audience already believes in ghosts, curses, evil spirits–the whole package. They believe their audience to be in such a vulnerable state already that they can get away with simply suggesting that maybe, possibly, according to somebody’s brother’s sister’s mailman’s uncle, there’s a ghost around here somewhere. The whole set operates off this idea that the area is scary because it is potentially haunted; the stories don’t give you any reason to believe in them–you have to be a believer already. And maybe that actually describes some people in Japan.

In any event, 8 yen per minute was a rip-off for Absolutely Real Scary Ghosts and Urban Legends DVD BOX. But at least I got this blog post out of it.

A few weeks ago I completed

A few weeks ago I completed  I’m most of the way through

I’m most of the way through  This is the fourth (and final) post in a series of posts about

This is the fourth (and final) post in a series of posts about

This is part three of a series of posts about

This is part three of a series of posts about  excited to get out and drive around.

excited to get out and drive around. This is part two of a series of articles about

This is part two of a series of articles about  five mile region, and it takes a while to drive around. While in the car, York speaks to the player about his past, his relationships with other characters, and old movies. Few games, let alone open world games, are able to work this much dialog in without stopping for cutscenes; according to the developers, York has over 3000 lines of dialog in Deadly Premonition, accounting for half of the total dialog in the game. Other games have used dialog this way before: Bioshock used reams of dialog to teach the player about key characters and the surrounding world, and

five mile region, and it takes a while to drive around. While in the car, York speaks to the player about his past, his relationships with other characters, and old movies. Few games, let alone open world games, are able to work this much dialog in without stopping for cutscenes; according to the developers, York has over 3000 lines of dialog in Deadly Premonition, accounting for half of the total dialog in the game. Other games have used dialog this way before: Bioshock used reams of dialog to teach the player about key characters and the surrounding world, and  I’ve been quiet for a while. I can legitimately blame this on work, and travel, and more work, but there is also another reason:

I’ve been quiet for a while. I can legitimately blame this on work, and travel, and more work, but there is also another reason:  summary of the previous episode.

summary of the previous episode. I’m writing this post from a hotel room in central London. I’m visiting the UK in order to attend the

I’m writing this post from a hotel room in central London. I’m visiting the UK in order to attend the  characters, and especially the narrative that they were willing to forgive and ignore absolutely egregious design and implementation failures. There are lots of other mediocre games that have better mechanics but duller story lines (like, say,

characters, and especially the narrative that they were willing to forgive and ignore absolutely egregious design and implementation failures. There are lots of other mediocre games that have better mechanics but duller story lines (like, say,

You might recall that about a year ago, I had the pleasure of attending and participating in the

You might recall that about a year ago, I had the pleasure of attending and participating in the