Trunks in a storage room

About four years ago I was working in the game industry making video games. At the time I was getting ready to start on a PSP game (this was before the PSP had shipped, but game development was already in full swing), and I wanted to get up to speed with my company’s 3D graphics engine. So I decided to make a couple of simple game demos to improve my understanding of the tech. First I made a 3D knock-off of an old NES puzzle game called Lot Lot, which worked out well but wasn’t very sexy. At the same time I was trying to pitch the idea that my company embark on a 3D adventure game (horror or not), so to back up that proposal I decided to build a 3D horror game demo using the company tech. My good friend (and fellow hardcore horror game fan) Casey Richardson agreed to make the art, and our goal was to spend a month or two and make something that was playable on PS2 and showed that this style of game could be accomplished without huge changes to our existing codebase.

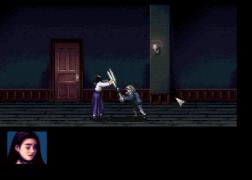

Since we were only working in our free time, the total duration of the project ended up being closer to three months (though we could have easily pulled it off in a month if we worked full time on it), but the result was pretty cool. What we ended up was an engine that supported fixed and tracking cameras, the Devil May Cry control scheme, dynamic lights and shadows, Silent Hill-esque film grain effects, and a pretty neat system for dynamically blending movement and animation to produce believable analog motion. We had a single test character named Trunks, which Casey hilariously made look like a pair of disconnected legs with a little bit of spine coming out of the severed hips, and a map containing a bunch of rooms that you could walk around and explore. Though we were just using test art (which turned out to be The Way To Go with this kind of game–see the next section), the game ran at 60fps and the game mechanics were immediately obvious to anybody who picked up the controller. Casey came up for the name: Terminal Station, taken from a 1954 film by Vittorio De Sica.

This exercise taught me tons of stuff about how survival horror games are made. One of the first things we learned was that placing regions in space that cause certain cameras to activate is way harder than it looks. You know how in Resident Evil you can run around and eventually see every corner of a given room because the various cameras in that room are set up to show different angles without overlapping? Yeah, setting that up is really hard. Casey did it by hand in the 3D modeling tool, but we quickly realized that a real game in this style would require a special tool to make camera regions. Otherwise it was too easy to make a room in which the player could walk off the screen, or simply be unable to explore a section of the space. Moving cameras make this a little bit easier, but it’s a much harder problem than I expected it would be.

Another thing we learned was that fixed camera games make so many real time 3D graphics problems easier. For example, our PS2 engine only allowed the character to be lit by 4 dynamic light sources at any given time, but we wanted to have rooms with a lot of localized lights (see the shot of the open refrigerator for an example). We realized that you can secretly turn lights on and off when the camera cuts and the player will never notice. This is a super simple solution and it worked great–we were able to make rooms with tons of lights and just link sets of four to specific camera angles. When playing the game, the player would appear to walk through the environment and be lit by all the lights in the room. We did the same thing with the shadow: the shadow can only be cast from one light (we only supported a single shadow), but depending on the angle of the camera we allowed which light was responsible for the shadow to change. That made it pretty easy to set up really dramatic shots without compromising the design of each room. (As an aside for the graphics programmers out there, this method also let us separate “shadow-receivable” geometry from “shadow-immune” geometry so our projective texture shadow only had to render a subset of the level art twice).

Though my company didn’t end up pursuing this style of game, I am extremely glad to have done this project because I learned tons about how many of the games listed on this site work. A lot of the code (or, more often, the general approach rather than the actual code) got reused in other projects (the blending motion and animation system survived for another year, only to be killed when the real game it was in got cancelled), and Casey and I learned a boatload. I’ll post some screenshots from our demo below. This isn’t a real game, and will never be a real game, it was just a learning exercise. But it was a lot of fun and it played pretty well!

Screenshots:

I bet you thought I just wasn’t going to post any more about the

I bet you thought I just wasn’t going to post any more about the