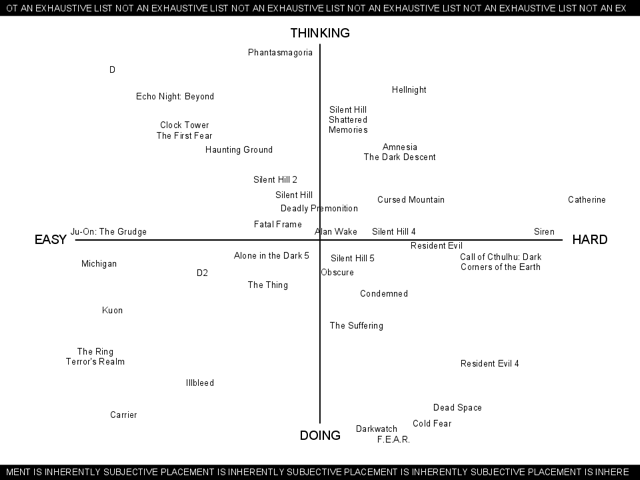

Today I received an e-mail from a guy named Ryan who, in the last 24 hours or so, has found himself at the center of a major internet debate about the classification of various horror games as either “survival horror” or “action horror.” The source of much internet angst is an collage Ryan assembled and posted on his blog. The image arranges games like Silent Hill, Resident Evil 1, Siren, and Amnesia on one side under the label “Survival Horror,” and places games like Dead Space, The Suffering, Dead Rising, F.E.A.R., and Resident Evil 4 on the opposite side under “Action Horror.” He posted it on Reddit (hey, remember Reddit?) and the comments section went crazy. A few hours later it showed up as an article on Kotaku (hey, remember Kotaku?), where the comments section also went crazy.

Today I received an e-mail from a guy named Ryan who, in the last 24 hours or so, has found himself at the center of a major internet debate about the classification of various horror games as either “survival horror” or “action horror.” The source of much internet angst is an collage Ryan assembled and posted on his blog. The image arranges games like Silent Hill, Resident Evil 1, Siren, and Amnesia on one side under the label “Survival Horror,” and places games like Dead Space, The Suffering, Dead Rising, F.E.A.R., and Resident Evil 4 on the opposite side under “Action Horror.” He posted it on Reddit (hey, remember Reddit?) and the comments section went crazy. A few hours later it showed up as an article on Kotaku (hey, remember Kotaku?), where the comments section also went crazy.

It is clear that Ryan has struck a nerve. His selections for the graphic have proved incredibly divisive; the Reddit story has a strong ranking of about 1000 votes, but that’s the result of 3000 up-ranks and 2000 down. Most of the comments there are about games he “missed,” or titles he incorrectly categorized. In his e-mail Ryan asked me to share some thoughts about it, so now I will, probably with about ten times the detail that Ryan was expecting. Seriously, he’s probably going to read this and think, “man, sorry I asked.” I’m not sorry, though, because his interesting graphic gets right to the heart of what this site is all about: understanding how horror games work at a fundamental level.

Vague Descriptors

I think that the argument surrounding Ryan’s graphic has a lot to do with the labels he’s chosen for his two columns: “survival horror” and “acton horror.” The definition of these terms is vague and imprecise, which is the root of many disagreements. For example, what does “survival horror” even mean? As a guy who runs a site with that term in the title, I can tell you from first-hand experience that it means a lot of different things to a lot of different people. Some associate it exclusively with Resident Evil, since that game coined the term. Others take it literally and apply it only to games where the protagonist is struggling to survive (thus excluding games like Echo Night and Clock Tower: The First Fear because health and saves are not rationed). Some people associate survival horror only with fixed cameras, pre-rendered backgrounds, and tank controls. Still others use it to mean any game with horror themes.

“Action horror” is even worse, as the phrase doesn’t even invoke a particular game. It’s a phrase that is obviously meant to contrast Resident Evil’s “survival horror,” but Resident Evil has tons of action! Almost every game in the series ends with a monster taking a missile to the face and a helicopter speeding away from a giant explosion! It’s not like we’re talking about the difference between The Capital and a Chow Yun Fat movie–the supposed opposite of “action horror” is a game with a lot of action. It’s more like this category is designed to discuss action in minute degrees. In Japan they have a chili oil called (and I shit you not) “Spicy Looking But Not Actually That Spicy Well A Little Bit Spicy Chili Oil.”. I feel like the difference between “survival horror” and “action horror” is like, “Some Action But Not All That Much But Still Actually Quite A Bit Of Action Horror Game.”

What

This? Totally not action.

I’m saying is, these are lousy terms.

Parsing Horror Design

Still, even if the terms are vague, Ryan’s on to something. There’s clearly a major difference in approach between, say, Amnesia: The Dark Descent and F.E.A.R. 3, even though both are first person horror games. There might be others ways to parse these games in order to better understand why they are different. In fact, that’s what this site is all about.

Turns out, there are a whole lot of ways to skin the horror design cat. Let’s take a look at a couple.

One way is to consider the frailty of the protagonist. The games on the left side of Ryan’s chart tend to star characters that are not particularly powerful, while those on the right tend to feature unstoppable muscle-bound agents of death. It stands to reason that frail, vulnerable characters can be put in danger more easily, and thus give rise to game mechanics that are more often flight than fight. Back in 2005 I wrote an article about this very topic. The problem with this approach is that all effective horror games, be they action-heavy or not, need to be able to put the protagonist (or, rarely, other characters) in danger. Even if the protagonist is a killing machine. Games like Resident Evil 4 and Dead Space do it by having increasingly huge, bombastic enemies. Leon is plagued by the unstoppable Chainsaw Man because that’s what it takes to put a badass like Leon in danger. So while frailty of the protagonist is certainly an interesting trait, it exists in almost every horror game to some degree, and thus isn’t a good candidate for categorization.

Perhaps a better way to parse these games is the system I’ve suggested before: “challenge format.” The idea is that some games challenge you to figure out what the next appropriate action is, while other games challenge you to actually complete that action. David Cage calls this “Journey and Mechanics,” and I’ve called it “Cognitive vs Mechanical challenges.” Another way to put it might be “mostly involving the brain” or “mostly involving the thumbs.” Devil May Cry is all about your thumbs; there’s no puzzle solving or meaningful story involved, just room after room of punishing hack-and-slash. Silent Hill, on the other hand, has combat but never makes it difficult. The challenge is to find your way through the town, to understand what is happening to the characters in the story, and to solve little puzzles along the way; stuff that involves your brain more than your thumbs.

I like the challenge format categorization a lot, but it’s imperfect too. It’s very rare for a game to be entirely mechanical or entirely cognitive in its challenge format; almost all are a blend between the two. An extreme example is Silent Hill: Shattered Memories, which swings wildly between the non-combat exploratory mode (cognitive) to the fast-paced, confusing running escape mode (mechanical). Resident Evil, too, has tons of puzzles and story for your brain to chew on but also features plenty of shooting and timing challenges. Fatal Frame’s combat mode is an entirely mechanical timing challenge, but the rest of the game is all cognitive stuff. The differences are only by degrees.

We might contort the challenge format idea into something about difficulty (e.g. the puzzle-heavy games tend to be harder to lose), but as one Redditor pointed out, many of these games have adjustable difficulty settings which dramatically change the game play. And yeah, we’ve talked about that here before too.

There’s a lot of meat here, and if you wanted to make a much more complicated graphic you could probably start to organize these games in terms of gradations of focus on different types of challenges. It would be some crazy graph and would probably blow your mind. Maybe there’s another angle we could use to approach this problem.

Brands of Horror

The one thing that ties all of these games together is that they fall into the thematic genre of horror. Now, genre in itself is neigh undefinable (quick, is Alien sci-fi or horror?), but let’s  just assume we all agree that we’re talking about games that all wave the horror banner. It turns out that there are many different kinds of horror, both within games and in the media at large. Perhaps the real difference between Ryan’s two columns has less to do with interactivity and more to do with the type of fear that the games intend to create.

just assume we all agree that we’re talking about games that all wave the horror banner. It turns out that there are many different kinds of horror, both within games and in the media at large. Perhaps the real difference between Ryan’s two columns has less to do with interactivity and more to do with the type of fear that the games intend to create.

Resident Evil, for example, is about inducing stress by putting the player in an increasingly dire situation. The nonsensical backstory doesn’t matter much because our primary concern when playing that game is how to get from point A to point B without running out of ammo, using any health items, and not getting killed.

Siren is also about stress, but its brand of horror comes from uncertainty. You know that the shibito will kill you if they find you, and you know that a particularly nasty one with bleeding eyes and a scythe is about to pass by the closet in which you are hiding. Will he open it? Did he see you jump in there a minute ago? This helplessness in the face of impending death is where Siren gets its (considerable) scares.

Silent Hill, on the other hand, isn’t really about combat (fighting isn’t very hard), and there’s rarely any ambiguity about the simulation. Instead, it’s about the implications of the backstory that makes the game tick. The narrative drops just enough clues for your brain to turn the resort town and it’s hellish reflection into a seriously scary place. Often, Silent Hill doesn’t even have to show you anything; they just pitch you the ball and with a little bit of prodding and manipulation, you knock it out of the park on your own.

Horror format is a really interesting way to look at these games. Condemned is about high-stakes, visceral close-quarter combat and descent into increasingly claustrophobic areas. The Thing is about protection and trust of NPC characters (well, it tries anyway). Left 4 Dead is about overwhelming odds. Catherine is about personal failure destroying your life and the line between sex and fear. Fatal Frame is about high-stakes combat combined with classical horror cues about ghosts and curses. Nanashi no Geemu is about personally assaulting you, the player, through the DS. In fact, when looking for a game that might be like some other game that you enjoyed, looking at the horror format (instead of the game play) might be the right way to go.

On the other hand, as a genre classification “brand of horror” is probably too specific. Almost every game has its own unique brand of horror!

The Fallacy of Categorization

This brings me to the one last point to make on this topic before I leave it alone.

Arguing about the correct categorization is ultimately futile because any sort of interesting category is going to be subjective. Arguing about the labels for a category is even more useless because labels change in meaning and popularity over time. You’ve seen the graph describing how the genre called “doom clone” was replaced by “first person shooter”, right?

This reminds me of the time I experimented with a baiting article about the “horror-ness” of Resident Evil 4, and found that people pretty much took the bait across the board.

Instead of deciding which column to file games in, let’s talk about why they are different. Let’s come up with a system, not just a few key phrases, that can identify the common traits of these games objectively. A proper dissection of this fascinating genre requires more than a quick “YOU GOT STALKER WRONG” comment on Reddit; it requires that we actually play these games and understand how they work.

Horror games are a goldmine of interesting ideas. They are worthy of a deeper discussion.

I’ve recently begun Noel Carroll‘s A Philosophy of Horror: Or, Paradoxes of the Heart, and though I’ve only just scratched the surface of the content I am already quite engrossed. Carroll’s intent is to take the horror genre, as defined by film and literature and other media, and put an academic lens to it; to cut the genre open and see how it works on the inside. Sounds familiar, right?

I’ve recently begun Noel Carroll‘s A Philosophy of Horror: Or, Paradoxes of the Heart, and though I’ve only just scratched the surface of the content I am already quite engrossed. Carroll’s intent is to take the horror genre, as defined by film and literature and other media, and put an academic lens to it; to cut the genre open and see how it works on the inside. Sounds familiar, right? Once upon a time, not too long ago really, the horror genre experienced something of a golden age. This is the period, beginning in 1996 with

Once upon a time, not too long ago really, the horror genre experienced something of a golden age. This is the period, beginning in 1996 with  the previous century.

the previous century. exudes the Silent Hill 2 vibe. The level design involves slowly opening up the map and then eventually descending deeper and deeper until we arrive at a very dark place, underground, mostly defenseless, with only the dim beam of a flashlight to guide us. The game even sounds like Silent Hill–the chord played when an item is collected is extremely similar to classic Silent Hill UI “accept” sounds. While playing the game I had a mental list of Silent Hill 2 references or influences going, but there are so many that I quickly lost track. Suffice it to say that Lone Survivor is covered with Silent Hill 2’s fingerprints.

exudes the Silent Hill 2 vibe. The level design involves slowly opening up the map and then eventually descending deeper and deeper until we arrive at a very dark place, underground, mostly defenseless, with only the dim beam of a flashlight to guide us. The game even sounds like Silent Hill–the chord played when an item is collected is extremely similar to classic Silent Hill UI “accept” sounds. While playing the game I had a mental list of Silent Hill 2 references or influences going, but there are so many that I quickly lost track. Suffice it to say that Lone Survivor is covered with Silent Hill 2’s fingerprints.

and producing serums requires that you collect extra vials, which are also spread out over the map. The only melee weapon is an axe, and it’s been designed to be hard to use. Clearly, End Night wants combat to be hard and risky; the game is designed to make the player want to avoid combat by whatever means necessary. More than anything else, this gives the game a bit of an old-school horror vibe.

and producing serums requires that you collect extra vials, which are also spread out over the map. The only melee weapon is an axe, and it’s been designed to be hard to use. Clearly, End Night wants combat to be hard and risky; the game is designed to make the player want to avoid combat by whatever means necessary. More than anything else, this gives the game a bit of an old-school horror vibe.

Today I received an e-mail from a guy named Ryan who, in the last 24 hours or so, has found himself at the center of a major internet debate about the classification of various horror games as either “survival horror” or “action horror.” The source of much internet angst is an collage Ryan assembled and

Today I received an e-mail from a guy named Ryan who, in the last 24 hours or so, has found himself at the center of a major internet debate about the classification of various horror games as either “survival horror” or “action horror.” The source of much internet angst is an collage Ryan assembled and

just assume we all agree that we’re talking about games that all wave the horror banner. It turns out that there are many different kinds of horror, both within games and in the media at large. Perhaps the real difference between Ryan’s two columns has less to do with interactivity and more to do with the type of fear that the games intend to create.

just assume we all agree that we’re talking about games that all wave the horror banner. It turns out that there are many different kinds of horror, both within games and in the media at large. Perhaps the real difference between Ryan’s two columns has less to do with interactivity and more to do with the type of fear that the games intend to create.

that a popular choice is a correct choice. If you can convince a person that people they associate themselves with act a certain way, they too will tend to act that way. To show how powerful the social proof can be, the authors ran an experiment involving the wording of a small sign placed in bathrooms throughout a hotel. The sign originally implored guests to reuse their towels to reduce water consumption in the name of saving Planet Earth. Cialdini changed the wording to suggest that most people who stayed in the room had decided to conserve energy by reusing their towels. He tracked the rate of towel reuse before and after the change, and found that by altering the wording of the sign he had improved towel reuse by 26%. The key was the “most people in this room” bit. By suggesting that other people who stayed in that very same room, people not unlike the guest himself, had reused their towels, he was able to convince more people to do the same.

that a popular choice is a correct choice. If you can convince a person that people they associate themselves with act a certain way, they too will tend to act that way. To show how powerful the social proof can be, the authors ran an experiment involving the wording of a small sign placed in bathrooms throughout a hotel. The sign originally implored guests to reuse their towels to reduce water consumption in the name of saving Planet Earth. Cialdini changed the wording to suggest that most people who stayed in the room had decided to conserve energy by reusing their towels. He tracked the rate of towel reuse before and after the change, and found that by altering the wording of the sign he had improved towel reuse by 26%. The key was the “most people in this room” bit. By suggesting that other people who stayed in that very same room, people not unlike the guest himself, had reused their towels, he was able to convince more people to do the same. like patient records–cool!). The idea, Jacob explained, is to make the player a more active participant in the game by casting them as authors (or at least purveyors) of snuff; combined with the handheld-camera kill display featured in the game, the instructions are designed to make you feel uncomfortably close to the content of the game.

like patient records–cool!). The idea, Jacob explained, is to make the player a more active participant in the game by casting them as authors (or at least purveyors) of snuff; combined with the handheld-camera kill display featured in the game, the instructions are designed to make you feel uncomfortably close to the content of the game.